[Please scroll down for the English version]

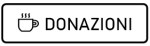

Ambientato nel mondo teatrale di Osaka, il film è dominato dal dispotismo di Daiei, il capo della compagnia, che decide di interrompere la storia d’amore tra il suo attore principale Shinzo (Kazuo Hasegawa) e la suonatrice di shamisen Hananryu (Isuzu Yamada) al fine di purificare l’impegno di Shinzo verso la sua arte.

Tra il 1938 e il 1944 Naruse dirige una serie di film dedicati al teatro, assecondando così i dettami patriottici e nazionalisti della Legge sul cinema, che imponeva un ritorno alla arti tradizionali, oltre a incoraggiare la produzione di opere basate su spirito di sacrificio, sottomissione e rispetto dei superiori.

The Way of Drama, per molti aspetti, è un film gemello di Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro: ritroviamo Kazuo Hasegawa nei panni di un artista che affina il proprio talento sottoponendosi a pratiche rigorose e Isuzu Yamada nel ruolo di suonatrice di shamisen (in cui Yamada eccelleva) costretta ad abbandonare il mondo teatrale.

Stilisticamente Naruse rinuncia agli sperimentalismi del film del 1938, in cui osava un nuovo stile mutuato dal modelli occidentali per reinterpretarlo secondo la propria sensibilità. The way of drama torna a una narrazione invisibile e a un montaggio che cuce impercettibilmente le pieghe del racconto. Il regista però persegue nella sua personale ricerca linguistica scandagliando le possibilità espressive della composizione dell’inquadratura, in particolare della profondità di campo. Il film contiene alcune immagini di elaborata raffinatezza, in cui la particolare disposizione degli arredi, la presenza di porte scorrevoli e il gioco degli elementi grafici (quadrettature, moduli) crea un singolare effetto di mise en abyme. L’effetto è disorientante e di meraviglia, e accresce la natura di finzione dell’opera.

Tanta delicatezza estetica non è né astratta né puramente decorativa, ma cela un ribollire di sentimenti umani posti di fronte all’evidenza di equivoci e menzogne. Shinzo e Hananryu sono entrambi vittime dell’industria teatrale – emblematizzata dalla tirannia del maestro Daiei, manipolatore e sessista – che considera l’artista come un soldato disposto a sacrificare tutto sul campo di battaglia. Non è un caso se Shinzo interpreta proprio il ruolo di un soldato che muore per la patria gridando “Lunga vita all’Imperatore!”. Velatamente, Naruse esprime una critica al Giappone militarista e nazionalista attraverso lo sguardo sulla spietata industria teatrale, pronta a “uccidere” ogni forma di individualismo. Eppure il teatro non è che un business (come dicono ripetutamente i personaggi del film) soggetto anche a volgari forme di concorrenza: il biglietto a metà prezzo, il coupon discount ricordano le “uova a 5 yen” del supermercato di Yearning (1964).

Come Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro, anche The Way of Drama è una riflessione sul rapporto tra spettacolo e reazione dello spettatore. In particolare, Naruse studia l’essenza del divismo mediante la presenza del carismatico Hasegawa, all’epoca tra le più grandi star del Giappone. Numerose inquadrature del pubblico colgono l’entusiasmo di fronte alle trascinanti apparizioni di Shinzo e la sua presa simbolica sull’immaginario.

Lo spazio ingombro e vitale del teatro viene filmato da precise angolazioni reiterate nel corso del film; e quella che sembra banale ripetizione di una tecnica è invece la più grande maestria di Naruse, ovvero la sua capacità di aggiungere intensità, stratificare la scena attraverso il filtro del tempo e delle emozioni umane.

Meno moderno di Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro, The Way of Drama tradisce la stanchezza di Naruse nel dover cedere, suo malgrado, alla retorica patriottica di quegli anni; ma il film è magistralmente disseminato di sottili osservazioni, dialoghi dalle incerte sfumature, dettagli che producono crepe all’interno del pensiero dominante. La bellezza di alcune sequenze ripaga degli aspetti più frustranti del film.

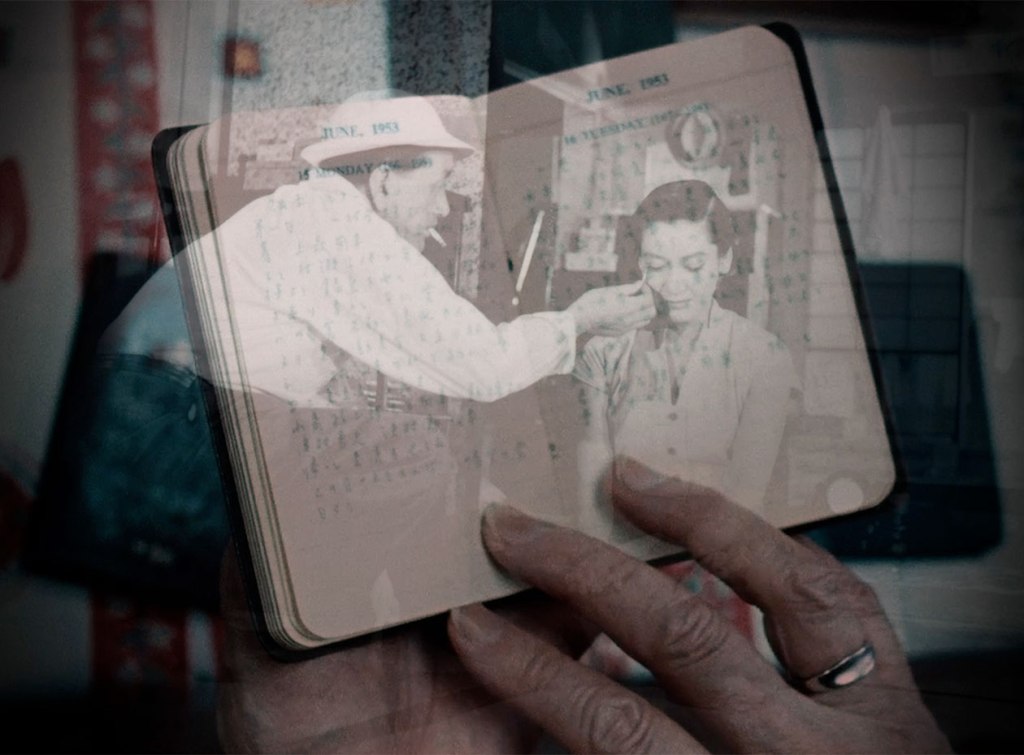

Memorabile, tra le altre, la scena della trasformazione di Shinzo in attore “classico” – tutta elaborata sull’uso della dissolvenza incrociata, che sembra darci accesso anche al mutamento spirituale del protagonista e alla densità sofferta dei suo pensieri; o la sequenza della danza, filmata con movimenti delicatissimi e continui, come se la macchina da presa danzasse assieme a Shinzo, assecondandone la grazia profonda. Molto belle anche le scene dedicate a Hananryu, il personaggio femminile che accetta il proprio martirio con onore e senza il più piccolo moto di ribellione (una figura molto diversa dalla volitiva Toyo del film del ’38). Spirituale e disincarnata, la ragazza scompare dal racconto, diventando nello sguardo di Naruse nulla più di un’ombra nella nebbia serale.

© Riproduzione riservata

English version

Set in the Osaka theater world, the film is dominated by the despotism of Daiei, the company’s master, who decides to end the romance between his lead actor Shinzo (Kazuo Hasegawa) and the shamisen player Hananryu (Isuzu Yamada) in order to make Shinzo a better artist.

Between 1938 and 1944, Naruse directed a series of films dedicated to the theater, thus fulfilling the patriotic and nationalist dictates of the Film Law, which mandated a return to traditional arts and encouraged the production of works based on a spirit of sacrifice, submission to rigorous discipline, and respect for superiors.

The Way of Drama, in many ways, echoes Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro: we find Kazuo Hasegawa as an artist honing his talent by undergoing rigorous training, and Isuzu Yamada as a shamisen player (in which Yamada excelled) forced to give up her art.

Stylistically, Naruse eschews the experimentalism of the 1938 film, in which he dared to adopt a new style borrowed from Western models, reinterpreting it according to his own sensibility. The Way of Drama returns to an invisible narration and an editing style that imperceptibly sews together the narrative’s folds. However, the director pursues his own linguistic exploration, studying the expressive possibilities of frame composition, particularly deep focus. The film contains some elaborately refined images, in which the particular arrangement of the furnishings, the presence of sliding doors, and the interplay of graphic elements create a singular mise en abyme. The effect is disorienting and astonishing, heightening the work’s fictional nature.

Such aesthetic attention is neither abstract nor purely decorative, but rather a vessel for intense human feelings confronted with the evidence of misunderstandings and lies. Shinzo and Hananryu are both victims of the theater industry—symbolized by the tyranny of the manipulative and sexist master Daiei—which views the artist as a soldier willing to sacrifice everything on the battlefield. It’s no coincidence that Shinzo plays the role of a soldier who dies for his country, shouting “Long live the Emperor!”

Naruse subtly expresses a critique of militaristic and nationalistic Japan through his look on the ruthless theater industry, poised to “kill” every form of individualism. Yet theater is nothing but a business (as the film’s characters repeatedly point out), also subject to vulgar forms of competition: half-price tickets and discount coupons recall the “5-yen eggs” in Yearning.

Like Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro, The Way of Drama is a reflection on the relationship between theatrical performance and audience reaction. In particular, Naruse explores the essence of stardom through the presence of the charismatic Hasegawa, one of Japan’s biggest stars at the time. Numerous shots of the audience capture their enthusiasm at Shinzo’s captivating performances and his symbolic hold on the imagination.

The cluttered, vibrant space of the theater is filmed from precise angles reiterated throughout the film; and what seems like a banal repetition of a technique is actually Naruse’s greatest mastery: his ability to add intensity, layering the scene through the filter of time and human emotion.

Less modern than Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro, The Way of Drama betrays Naruse’s weariness at having to give in, against his will, to the patriotic rhetoric of those years; But the film is masterfully peppered with subtle observations, nuanced dialogue, and details that create cracks within the propaganda. The beauty of some sequences makes up for the film’s more frustrating aspects.

Memorable, among others, is the scene of Shinzo’s transformation into a “classical” actor—completely crafted with the use of cross-fades, which seem to give us access to the protagonist’s spiritual transformation and the painful density of his thoughts; or the dance sequence, filmed with delicate, continuous movements, as if the camera were dancing alongside Shinzo, following his profound grace.

Equally beautiful are the scenes dedicated to Hananryu, the female character who accepts her martyrdom with honor and without the slightest hint of rebellion (a very different figure from the strong-willed Toyo of the 1938 film). Spiritual and disembodied, the woman disappears from the story, becoming nothing more than a shadow in the evening mist.

Lascia un commento