[Please scroll down for the English version]

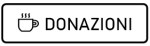

Hideo Suzuki, un assistente mangaka trentacinquenne considerato un fallito, deve affrontare un’invasione zombie a Tokyo. Mentre nel mondo si scatena l’apocalisse, Hideo si ritrova a combattere per sopravvivere e a diventare un eroe suo malgrado. Dal manga di Kengo Hanazawa.

Nel 2013 Hollywood produce World War Z, ipertrofico e costosissimo polpettone privo di tensione e di ispirazione, girato in modo impersonale all’insegna di una bulimia (più comparse, più azione, più tagli di montaggio) che satura lo schermo di insignificanza; un horror per caso, un action in cui la teatralità del “mostro” (ridicolo e dilettantesco, negli effetti quanto nei movimenti) è un equivoco nei confronti di un genere che non viene compreso.

A due anni di distanza la Corea del sud e il Giappone rispondono con due zombie movie differenti ma strabilianti e innovativi, che pur muovendosi all’interno dei codici del genere appaiono nuovi e intensamente personali: Train to Busan di Yeon Sang-ho è un’opera concentratissima e spettacolare, ma anche tinta di dolore e senso struggente di impotenza; un film molto amato da un pubblico trasversale per la presenza di un melodramma “alto” e universale all’interno della struttura orrorifica.

I am a hero di Shinsuke Satō è invece molto più ondivago e strutturalmente libero. Privo del rigore di Train to Busan e del suo crescendo emotivo-spettacolare (ottenuto con una gestione stupefacente del tempo e dello spazio e un’attenzione privilegiata ai rapporti tra i personaggi), I am a hero dà forma cinematografica a una nazione in crisi, in cui un antieroe irresoluto e inerte si aggira stupefatto in un paesaggio desertificato e irriconoscibile.

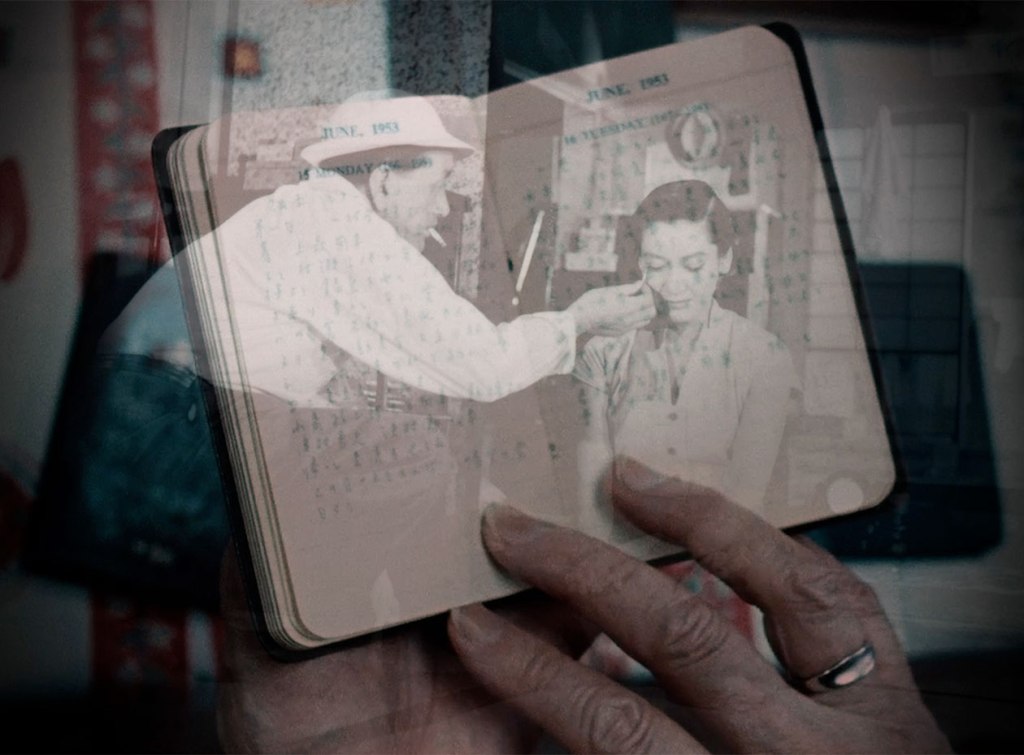

Il volto urbano del Giappone acquista una qualità stralunata e western in cui gli zombie, ancora legati al proprio passato, rivivono la loro condizione terrena bloccati in una coazione a ripetere. Lo zombie diviene emblema di alienazione, scarto di una società che priva gli esseri umani di un’identità e li riduce a morti viventi: c’è lo zombie-salaryman in giacca e cravatta, convinto di trovarsi in uno dei tanti treni che lo condurranno al lavoro; lo sportivo che rincorre il perfetto salto in alto, schiantandosi ripetutamente al suolo; la fashion victim dipendente dallo shopping; e c’è anche qualche zombie indefinibile – donne-ragno che camminano su otto zampe o creature bruciate come il carbone – perché, come afferma un personaggio, “alcuni non possono essere spiegati, proprio come gli umani”.

Come spesso accade nell’horror giapponese, la società è all’origine del male e della mutazione: che si tratti dell’uomo di metallo Tetsuo, figlio della metropoli tossica e industriale, o dell’insegnante-assassino di Battle Royale, plasmato da una violenta cultura della competizione, è la stessa nazione a produrre le sue malformazioni.

In I am a hero è un virus a trasformare gli esseri umani in zombie – un topos fedelmente assecondato – ma è evidente l’aperta condanna del regista nei confronti di un paese che sacrifica i propri abitanti all’ideologia di una produttività massimizzata allo stremo. Nemmeno la morte libera dalla schiavitù del ruolo: in I am a hero lo zombie rivive, in chiave parodistica e ossessiva, la frustrazione sperimentata in vita.

Poco preoccupato di mantenere tensione narrativa o coerenza del racconto, il regista alterna lunghe scene di dialogo e inazione a momenti di spettacolo grandiosi e dinamici. In particolare, la prima grande scena di massa, con un attacco zombie nelle strade di una Tokyo periferica e cementificata, è girata con lunghi piani sequenza (quasi “One cut of the dead”!) in cui Shinsuke Satō sembra divertirsi molto, dando sfogo a tutta la sua inventiva. Lunghi carrelli in avanti e indietro, frenetici one takes macchina a mano e composizioni dalla sofisticata profondità di campo si susseguono nella creazione di uno spazio reinventato e astratto. L’effetto da teatro dell’assurdo, con personaggi che piombano in scena cadendo dall’alto, o entrano da non ben specificati fuori campo (emblemi di un ignoto minaccioso che preme sugli spazi urbani), conferisce alla scena un carattere di surreale smarrimento, in cui angoscia e strepitose gag corporali concorrono nel creare un senso di esaltata eccitazione.

Il nostro antieroe Hideo (un bravissimo Yō Oizumi) si muove tra i tanti momenti d’azione e le stasi atemporali (durante le quali approfondisce il rapporto con Hiromi-chan, gentile studentessa poi mutata in dolente creatura di mezzo) sentendosi del tutto fuori posto, non abbastanza coraggioso per combattere né sufficientemente codardo per darsi alla fuga. Timido mangaka fallimentare e velleitario, Hideo è un passivo ricettacolo dell’orrore a cui assiste, un uomo comune come lo era Ash della trilogia di Evil Dead. E se nei film di Raimi il commesso Ash risorgeva in un nuovo corpo eroico, con una motosega al posto della mano destra, Hideo finirà col trasformarsi in un combattente munito di fucile-prolungamento del proprio corpo, ma non prima di aver sperimentato una pioggia di sangue e terrore.

I am a hero alterna dolcezza, divertimento e crudeltà. Il gore è estremo e cromaticamente intenso, gli assalti ipercinetici e inventivi, tra ralenti, voli al suono del valzer di Strauss e azione coreografata. Il tutto è pervaso d’amore per una città fatiscente e vuota, costellata di centri commerciali e negozi colorati, scheletri pop in cui gli zombie anelano nostalgicamente a un ritorno. Si ride e ci si commuove per questi mostri incolpevoli, tristi impiegati con un unico ricordo: il lavoro.

© Riproduzione riservata

English Version

In 2013, Hollywood produced World War Z, a hypertrophic and exorbitantly expensive mishmash devoid of tension or inspiration, shot in an impersonal way under the banner of a certain bulimia (more extras, more action, more cuts) that saturates the screen with insignificance; a horror film by accident, an action movie in which the theatricality of the “monster” (ridiculous and amateurish, both in its effects and in its movements) becomes a misunderstanding of a genre that is not truly understood.

Two years later, South Korea and Japan replied with two zombie movies that were very different yet both astonishing and innovative—works that, while moving within the codes of the genre, appear fresh and deeply personal: Yeon Sang-ho’s Train to Busan is a tightly focused and spectacular piece, yet also suffused with pain and a poignant sense of helplessness; a film widely loved by a diverse audience for the presence of a “high,” universal melodrama within its horror framework. Shinsuke Sato’s I Am a Hero, on the other hand, is far more erratic and structurally free. Lacking the rigor of Train to Busan and its emotional-spectacular crescendo (achieved through a stunning command of time and space and a keen focus on relationships among characters), I Am a Hero gives cinematic shape to a nation in crisis, where a hesitant, inert antihero wanders in bewilderment through a desolate and unrecognizable landscape.

The urban face of Japan takes on a bizarre, almost Western quality, where zombies—still bound to their past—are trapped in a compulsive repetition of what was once their condition.

The zombie becomes an emblem of alienation, a byproduct of a society that strips human beings of identity and reduces them to the living dead: there is the salaryman-zombie in suit and tie, convinced he’s on one of the countless trains taking him to work; the athlete who keeps chasing the perfect high jump, crashing to the ground over and over; the fashion victim addicted to shopping; and there are even unclassifiable zombies—spider-women running on eight legs or creatures burned black as coal—because, as one character remarks, “some can’t be explained, just like humans.”

As often happens in Japanese horror, society itself lies at the origin of evil and mutation: whether it’s the metal man Tetsuo, child of a toxic or industrial metropolis, or the teacher-assassin of Battle Royale, molded by a violent culture of competition, it is the nation itself that breeds its own deformities. In I Am a Hero it’s a virus that turns humans into zombies—a faithfully followed topos—but the director’s open condemnation of a country that sacrifices its citizens to an ideology of extreme productivity is unmistakable. Not even death frees one from the slavery of roles: in I Am a Hero the zombie relives, in parodic and obsessive fashion, the same frustrations it endured in life.

Unconcerned with maintaining narrative tension or consistency, the director alternates long scenes of dialogue and stillness with grand and dynamic spectacles. In particular, the first large-scale scene—an outbreak in the cemented outskirts of Tokyo—is shot in long takes (almost One Cut of the Dead style!) where Shinsuke Sato seems to be having great fun, unleashing his full inventiveness. Long tracking shots forward and backward, frantic handheld one-takes, and compositions with sophisticated depth of field follow one another in the creation of a reinvented, abstract space. The effect of the theater of the absurd—with characters dropping into the frame from above or entering from unspecified off-screen spaces (emblems of an ominous unknown pressing against urban confines)—gives the sequence a quality of surreal disorientation, where anxiety and spectacular physical gags combine to create a feeling of ecstatic exhilaration.

Our antihero Hideo (an excellent Yo Oizumi) moves between bursts of action and atemporal pauses (during which he deepens his relationship with Hiromi-chan, a gentle student later transformed into a sorrowful creature of the in-between), feeling completely out of place—not brave enough to fight, yet not cowardly enough to flee. A shy, failed, and self-deluding mangaka, Hideo is a passive receptacle of the horror unfolding before him, an ordinary man much like Ash from Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead trilogy. And if Raimi’s shop clerk Ash rose again in a new heroic body, with a chainsaw for a right hand, Hideo will in turn become a fighter armed with a rifle—an extension of his own body—but only after enduring a rain of blood and terror.

I Am a Hero oscillates between tenderness, humor, and cruelty. The gore is extreme and chromatically vivid; the attacks hyperkinetic and inventive, moving between slow motion and choreographed action. The entire film is suffused with love for a decaying, empty city dotted with shopping malls and brightly colored stores—pop skeletons where the zombies nostalgically yearn to return. One laughs and grows moved by these innocent monsters, sad office workers with a single remaining memory: their job.

Lascia un commento