[Please scroll down for the english version]

Kurata è un giovane sceneggiatore che lavora a una serie televisiva. Un giorno riceve la visita di Yui, una ragazza che afferma di essere sua nipote, tornata indietro nel tempo di cinquant’anni. Yui ha una missione: convincerlo a riscrivere il finale della sua sceneggiatura. Perché se non lo farà, le serie televisive scompariranno del tutto.

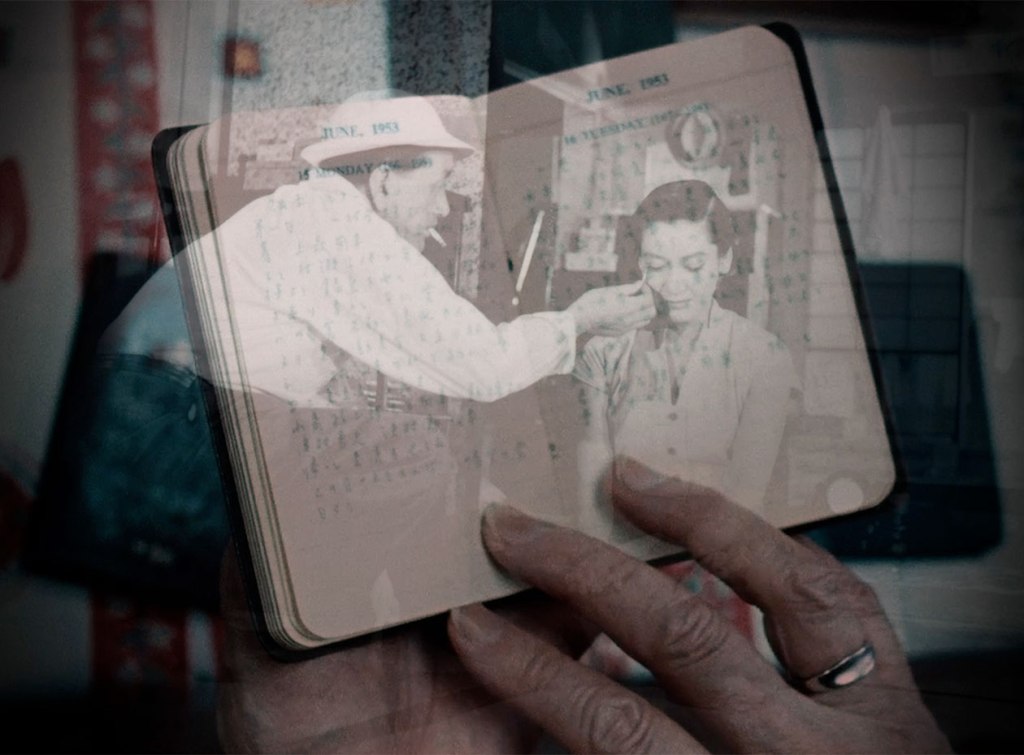

Koreeda aderisce alla campagna “Shot on iPhone” di Apple e trasforma un piccolo corto promozionale in una dichiarazione d’amore alle serie televisive e alla “gente comune” che la serialità mette al centro delle proprie storie. Proprio Koreeda ha trovato nella televisione (per la quale ha realizzato diverse opere seriali, fino alle recenti Makanai e Asura) un territorio di libertà in cui confrontarsi con codici stilistici, sperimentare nuovi concetti di durata e struttura narrativa, adeguarsi a un linguaggio più accessibile senza però rinunciare a un’impronta autoriale. E Last Scene sembra voler rendere omaggio alla leggerezza ariosa delle serie, al loro sguardo ravvicinato sugli esseri umani, scrutati nei gesti quotidiani, nella dolcezza di un pasto consumato insieme o nella scoperta pudica di un sentimento.

Sfruttando l’espediente dei “viaggi nel tempo” il regista mette a fuoco un’acuta quanto affettuosa riflessione metatelevisiva che prevede una personale reinterpretazione, con spirito ludico, dei codici classici dei j-drama: dalla fotografia limpida e luminosa, a un’atmosfera di trasalimento e scoperta, sino a vari topoi stilistici e tematici compresa la “passeggiata sulla spiaggia” (che è anche un luogo prediletto dal regista) come metafora di sentimenti in tumulto. Ma allo stesso tempo il regista infonde, in quest’elenco familiare di segni e simboli, il velo di una riflessione più profonda, che concerne ruoli e forme della narrazione.

È, la serie tv, solamente un “prodotto”, un oggetto di consumo commerciale come afferma Kurata? O è qualcosa che può addirittura condizionare il nostro futuro (incarnato da Yui) in virtù delle sue radici profonde nell’immaginario collettivo?

In fondo i drama televisivi, proprio per la loro immediatezza e per un destino produttivo di “istantaneità”, riescono a cogliere i desideri umani nel loro farsi e a seguirne dolcemente le onde. Puntata dopo puntata registrano la marea di un immaginario che cresce e si quieta, sottoposto alla spinta del tempo. Koreeda attribuisce scherzosamente un valore salvifico all’ultima scena forse proprio per alludere alla funzione di “custodi dei sogni” delle varie forme di narrazione, incluse le più semplici e popolari. Se la serie di Kurama dovesse fallire, non solo sparirebbero “tutte le serie future”, ma forse anche la capacità di sognare, emblematizzata dalla ruota delle meraviglie su cui Yui è così ansiosa di salire.

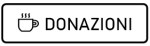

Koreeda si muove tra semplici diners e luna park, si avvicina ai suoi protagonisti con primi piani sinceri e diretti, rendendoci partecipi di sentimenti tremuli e pronti a svanire con una dissolvenza. Il suo Last Scene accoglie le forme del cinema e della televisione, si adatta con entusiasmo ai nuovi mezzi tecnologici, riconosce la traccia indelebile lasciata dagli anime sull’immaginario; ha i cieli azzurri di Shinkai e la malinconia dello Studio Ghibli, in particolare di Quando c’era Marnie (2014), con cui condivide i paradossi temporali. Takumi non può sfuggire all’amore e al sogno, senza rimpianti, come gli infiniti spettatori che attendono una nuova puntata del loro drama preferito: “anche se ci separiamo oggi, tu vivrai ancora, in me, domani”.

Corto in streaming qui:

English Version

Kurata is a young screenwriter working on a television series. One day he receives a visit from Yui, a girl who claims to be his niece and who has travelled back in time by fifty years. Yui has a mission: to convince him to rewrite the ending of his script. Because if he doesn’t, television series will disappear altogether.

Koreeda joins Apple’s “Shot on iPhone” campaign and transforms a promotional short into a declaration of love for television dramas and for the “ordinary people” that serial storytelling places at the heart of its narratives. Koreeda himself has found in television — for which he has created several serial works, up to the recent Makanai and Asura — a space of freedom in which to explore stylistic codes, experiment with new concepts of duration and narrative structure, and adapt to a more accessible language without sacrificing an authorial imprint. Last Scene seems intent on paying homage to the airy lightness of TV series, to their close-up gaze on human beings, observed in everyday gestures, in the sweetness of a shared meal, or in the shy awakening of a feeling.

By employing the device of “time travel,” the director shapes a sharp yet affectionate metatelevisual reflection that includes a playful reinterpretation of the classic j-drama codes: from clear, luminous cinematography to an atmosphere of wonder and discovery, all the way to various stylistic and thematic topoi, including the “walk on the beach” (a setting dear to the director) as a metaphor for emotions in turmoil. At the same time, the director casts over this familiar list of signs and symbols a veil of deeper reflection concerning the roles and forms of storytelling.

Is the TV series merely a “product,” a commercial good as Kurata claims? Or is it something that can even shape our future (embodied by Yui) thanks to its deep roots in the collective imagination?

Television dramas, precisely because of their immediacy and their “instantaneous” production fate, manage to capture human desires as they form and gently follow their waves. Episode after episode, they record the tide of an imagination that rises and settles, pushed along by time. Koreeda humorously assigns a salvific value to the last scene, perhaps to suggest the role of storytelling— even in its simplest and most popular forms — as a “guardian of dreams.” If Kurata’s series were to fail, not only would “all future series” disappear, but perhaps also the ability to dream, symbolised by the Ferris wheel that Yui is so eager to ride.

Koreeda moves between simple diners and amusement parks, approaching his characters with sincere, direct close-ups and allowing us to share in fragile feelings ready to fade out like a dissolve. His Last Scene embraces the forms of cinema and television, enthusiastically adapts to new technologies, and acknowledges the indelible mark left by anime on the imagination; it carries the blue skies of Shinkai and the melancholy of Studio Ghibli — particularly When Marnie Was There (2014), with which it shares temporal paradoxes. Takumi cannot escape love and dreams, without regret, just like the countless viewers waiting for the next episode of their favourite drama: “even if we part today, you will still live on, within me, tomorrow.”

Lascia un commento