[Please scroll down for the English Version]

Kihachi, un lavoratore disoccupato, vaga per le pianure industriali di Tokyo con i suoi due figli piccoli, Zenko e Masako. La notte i tre si accampano in una locanda affollata, dove Kihachi conosce una giovane donna di cui si invaghisce, Otaka, anche lei disoccupata e madre di una bambina, Kimiko.

La produzione di An Inn in Tokyo è molto travagliata, ma nonostante le difficoltà economiche Ozu gira un film bellissimo. Ultimo capitolo della serie di Kihachi, l’opera è uno sguardo, attraverso la sensibilità del regista e la sua prediletta reticenza, sulla profonda recessione del periodo: uomini, donne e bambini sono erranti e muti, senza un tetto né cibo; la disperazione viene rappresentata attraverso i sentimenti di Kihachi.

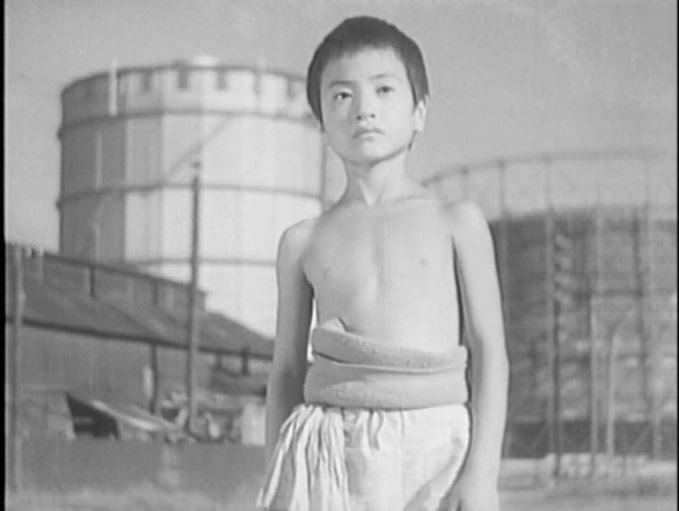

Ambientato nella desolazione delle pianure ai margini di Tokyo, prive di vita e dominate dalla presenza di fabbriche, silos, ciminiere perennemente sbuffanti e pali della luce, il film ne attraversa i campi aridi e scabri per creare un’estetica industriale formalmente curatissima e significante. Siamo di fronte ad un lavoro unico per quanto riguarda la stilizzazione, la composizione rigorosa delle inquadrature, il montaggio ritmico e la progressiva rarefazione della realtà attraverso pillow shots (immagini di transizione). Il realismo di Ozu è paradossalmente ottenuto attraverso immagini anti-realistiche che acquistano un valore universale. An Inn in Tokyo è cinema di straordinario nitore in cui le cose, nella loro evidenza concreta, sono parte di un disegno di astrazione formale che vede gli esseri umani “abitare” la trascendenza.

Tre protagonisti: il nostro Kihachi (Takeshi Sakamoto), con la sua indole pigra e contraddittoria, i gesti impulsivi, i tratti di infantile irresponsabilità immediatamente seguiti da commosse prese di coscienza; i suoi figli Zenko (un Tomio Aoki notevolissimo, un interprete che si conferma per il cinema dei bambini di Ozu ciò che Chishū Ryū rappresenta per il cinema della maturità) e il piccolo Masako. Ozu li inquadra nel loro vagabondare su sentieri pietrosi: le figure umane camminano all’unisono e sono incorniciate nell’inquadratura da “filari” di pali della luce. Coltri di fumo si sollevano dalle fabbriche, l’aria pesa nel silenzio, gru e capannoni sono apparizioni stralunate e metafisiche. All’afflizione muta di Kihachi, uomo dei margini, dagli abiti sporchi e dall’atteggiamento perdente, fa da controcanto la spontanea vivacità dei due ragazzi, che senza troppo perdersi d’animo guadagnano piccole somme catturando cani randagi. E’ una famiglia povera, ma unita: Ozu li riprende spesso di spalle, o seduti, e in ogni inquadratura ne evidenzia la basilare somiglianza della postura e dei gesti.

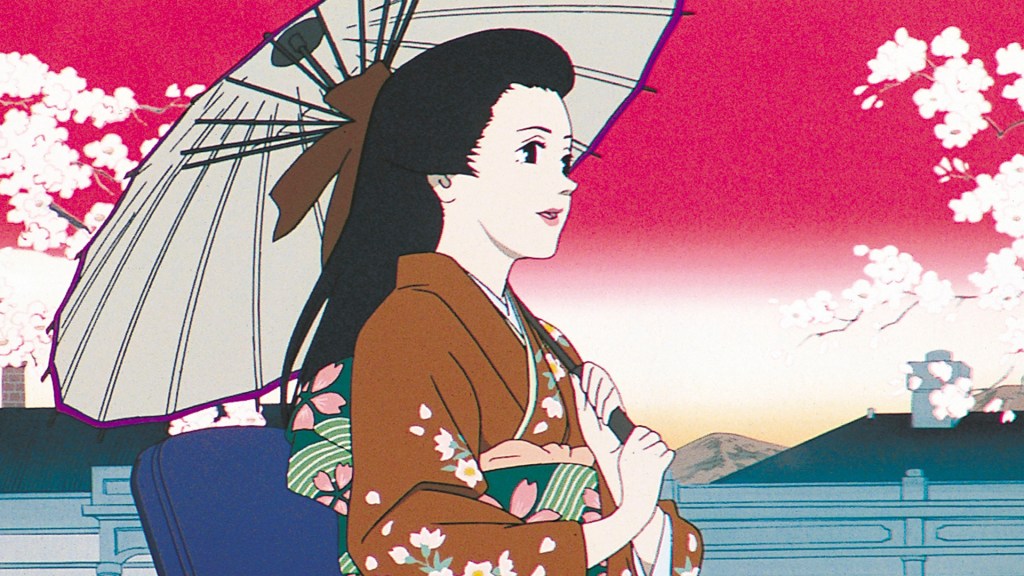

Di sera, i tre trovano riparo in una locanda affollata: e qui Ozu ci fa letteralmente “sentire” la povertà, al punto che ne percepiamo odori, rumori, l’umidità delle pareti o la durezza del pavimento. Illuminata da una nuda lampadina, la stanza pullula di persone: sdraiate, sedute, di ogni età. Entra in scena la giovane Otaka (Yoshiko Okada), anche lei alla ricerca di un lavoro per poter sfamare sua figlia Kimiko. Kihachi si innamora di lei: la donna lo scuote dalla passiva rassegnazione e innesca il suo riscatto.

Il film contiene temi che saranno ripresi anche nella filmografia successiva, come la discesa di Otaka nella prostituzione per salvare la figlia malata (si veda Una gallina nel vento) ma anche la sua disperazione di giovane donna abbandonata a se stessa (come in Crepuscolo di Tokyo). E’ un film nero sotto tanti aspetti, duro e quasi senza speranza, se non fosse per la dolcezza e l’innocenza dei bambini protagonisti, ai quali Ozu dedica sequenze magnifiche: i giochi su grandi ruote abbandonate, tra i silos; l’allegria delle voci che risuonano – ci sembra quasi di sentirle – nelle pianure brulle e funebri. In qualunque situazione, i figli di Kihachi invitano all’ottimismo: “domani ce la faremo!”.

Memorabile la scena in cui Zenko, per confortare il padre (questi padri deludenti e avviliti, proni all’inerzia di un’ubriacatura di sakè) allestisce per lui un pic nic immaginario. La grazia di questa sequenza fatta di illusioni, con i due personaggi inquadrati l’uno di fronte all’altro, di cui vediamo la gioia dei corpi alle prese con cibo delizioso e irreale, non sarebbe possibile senza la sensibilità dei due eccezionali interpreti.

Nel finale, riluce il personaggio di Otsune, interpretata da Iida Chōko, qui non ancora trentenne ma in grado di conferire al suo ruolo il senso di un’esperienza mite, umile e silenziosa, colma di dolore rassegnato di fronte all’addio di Kihachi: il suo pianto, col viso nascosto tra le mani (un gesto caro a Ozu), è straziante; il suo destino di solitudine è tragico quanto quello dell’uomo, che si allontana dicendo: “è terribile essere poveri”.

English Version

Kihachi, an unemployed laborer, wanders across the industrial plains of Tokyo with his two young children, Zenko and Masako. At night the three camp in a crowded inn, where Kihachi meets a young woman he becomes infatuated with, Otaka, herself unemployed and mother to a little girl, Kimiko.

The production of An Inn in Tokyo was extremely troubled, yet despite the financial difficulties Ozu created a beautiful film. The last chapter in the “Kihachi series,” the work is a gaze—filtered through the director’s sensibility and his beloved reticence—at the deep recession of the time: men, women, and children wander silently, without shelter or food; despair is represented through Kihachi’s feelings. Set amid the desolation of the plains on Tokyo’s outskirts—lifeless stretches dominated by factories, silos, ever-smoking chimneys, and rows of utility poles—the film traverses those barren, scraped-clean fields to create an industrial aesthetic that is exquisitely crafted and full of meaning. We are faced with a unique work in terms of stylization, the rigorous composition of shots, rhythmic editing, and the progressive rarefaction of reality through pillow shots (transitional images). Ozu’s realism is paradoxically achieved through anti-realistic images that acquire universal value. An Inn in Tokyo is cinema of extraordinary clarity, in which things, in their concrete presence, become part of a design of formal abstraction that allows human beings to “inhabit” transcendence.

There are three protagonists: our Kihachi (Takeshi Sakamoto), with his lazy and contradictory nature, impulsive gestures, and hints of childish irresponsibility immediately followed by moved awakenings of conscience; his son Zenko (a remarkable Tomio Aoki—an actor who proves himself to be for Ozu’s cinema of childhood what Chishū Ryū is for the cinema of maturity); and little Masako. Ozu frames them as they wander along rocky paths: human figures walking in unison, bordered within the frame by “rows” of utility poles. Sheets of smoke rise from the factories, the air grows heavy in the silence, cranes and warehouses appear as uncanny, metaphysical presences. Against the mute affliction of Kihachi—a marginal man with dirty clothes and a defeated posture—stands the spontaneous liveliness of his two boys, who, without becoming too discouraged, earn small sums by catching stray dogs. They are a poor but united family: Ozu often films them from behind, or seated, and in every shot he highlights their fundamental resemblance in posture and gesture.

In the evenings, the three seek shelter in a crowded inn, and here Ozu makes us literally feel the poverty—to the point that we can perceive its smells, noises, the dampness of the walls, the hardness of the floor. Lit by a bare bulb, the room swarms with people: lying down, sitting, of all ages. Into this space enters the young Otaka (Yoshiko Okada), also searching for work to feed her daughter Kimiko. Kihachi falls in love with her: she shakes him out of his passive resignation and sparks his redemption.

The film holds themes Ozu would revisit in later works, such as Otaka’s descent into prostitution to save her sick daughter (see A Hen in the Wind), but also her despair as a young woman abandoned to herself (as in Tokyo Twilight). In many respects, it is a dark film—harsh and nearly hopeless—were it not for the sweetness and innocence of the children, to whom Ozu dedicates magnificent sequences: their games on large abandoned wheels among the silos; the cheerfulness of voices that echo—almost audible to us—across the barren, funereal plains. Whatever the situation, Kihachi’s sons bring an invitation to optimism: “Tomorrow we’ll make it!”

Unforgettable is the scene in which Zenko, trying to comfort his father (one of those disappointing, dejected fathers numbed by a sake-induced inertia), sets up an imaginary picnic for him. The grace of this illusion-laden sequence—with the two characters framed facing each other, their bodies delighting in delicious, unreal food—would not have been possible without the sensitivity of the two exceptional performers.

In the finale, the figure of Otsune glows. Played by Iida Chōko, here not yet thirty but capable of giving her role the sense of gentle, humble, silent experience—heavy with resigned sorrow before Kihachi’s departure—she is heartbreaking: her weeping, face hidden in her hands (a gesture dear to Ozu), is devastating. Her destiny of solitude is as tragic as the man’s, as he walks away saying, “It’s terrible to be poor.”

© Riproduzione riservata

Lascia un commento