[Please scroll down for the english version]

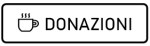

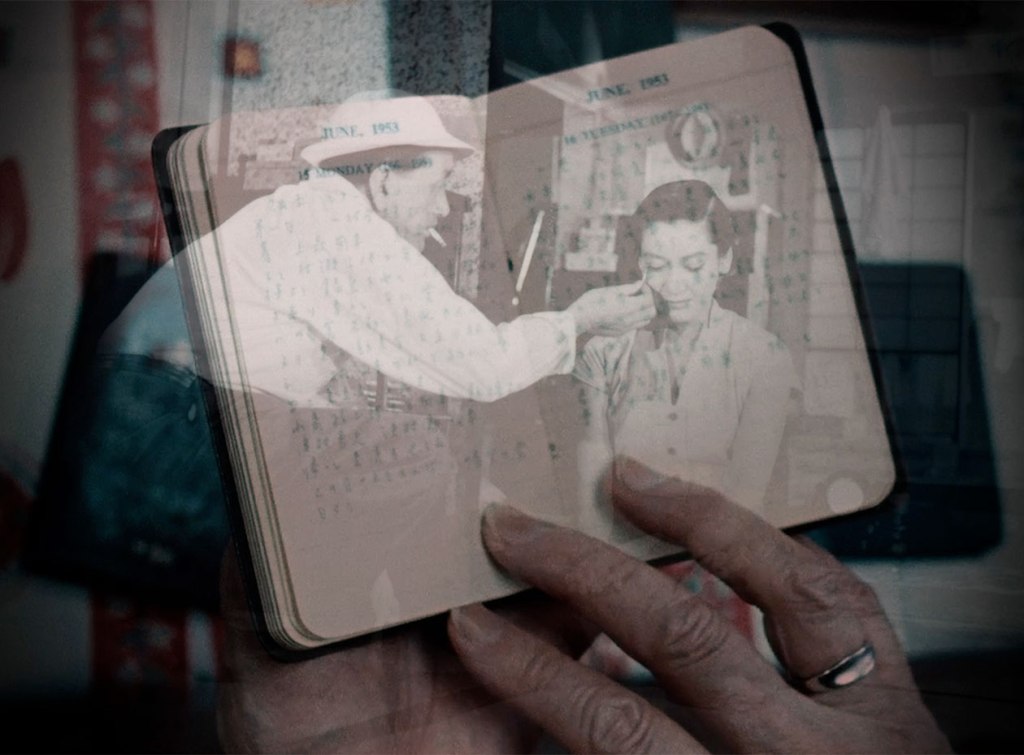

Film del 1954 e ultimo film di Mizoguchi interpretato da Kinuyo Tanaka, che per il regista incarnò moltissimi personaggi differenti – geishe, contadine, mogli ridotte in povertà, amanti tradite, prostitute, madri – donando a ciascuna di loro un carattere intenso e unico, complesso e chiaroscurale. Mizoguchi spesso confinò le sue figure femminili in un astratto idealismo e martirio; ma Tanaka era un’artista troppo intelligente per non sfuggire a tale prigionia attraverso la ricchezza densa e profonda, talora misterica, delle proprie interpretazioni. Anche Hatsuko, la “mistress” di The Woman in the Rumor, è una donna dalla personalità sfumata. Coordinatrice inflessibile di un bordello di lusso – una tradizione di famiglia che rivendica con orgoglio – Hatsuko conosce però i tormenti e l’infelicità dell’amore, e nutre segretamente il sogno di una vita “rispettabile” e di un impossibile matrimonio con un dottore più giovane di lei. Nel bordello è ospite la figlia di Hatsuko, Yukiko: una ragazza dall’aspetto elegante e urbano (interpretata da Yoshiko Kuga) , istruita e sensibile, ostile alla professione materna che però le ha consentito di portare a termine gli studi. Anche Yukiko è dunque un personaggio che vive di tensioni opposte e inconciliabili, divisa tra il privilegio della propria posizione ed il disprezzo per l’attività del bordello, che di quella posizione è il fondamento economico.

Mizoguchi, nel tratteggiare con grande finezza ogni aspetto delle due protagoniste – dai kimono variopinti e sensuali della sorridente Hatsuko ai completi scuri e rigorosi di una silenziosa e ombrosa Yukiko – ci pone davanti a due caratteri che mutano davanti ai nostri occhi, talora ponendosi in aperta opposizione, altre volte confondendosi fino a scambiarsi i ruoli. Entrambe innamorate del giovane ed opportunista dottore (un altro di quei personaggi maschili vili e mediocri che costellano la filmografia di Mizoguchi), madre e figlia troveranno nel sentimento la chiave per mettersi reciprocamente a nudo, scarnificarsi, fino a rivelare un nucleo di verità che le porterà a comprendersi e avvicinarsi. Le due donne diventano quindi parte di un’unica personalità femminile dalla natura multiforme: istintiva e materna, passionale e protettiva, cinica e innocente al tempo stesso. Questo confronto graduale, via via più intenso sino a diventare emotivamente sconvolgente tanto per i personaggi quanto per lo spettatore, prende vita in un contesto spaziale – quello dell’ampio e labirintico bordello – che Mizoguchi filma con una maestria a sua volta imperscrutabile e rarefatta. La sua macchina da presa si pone a distanza per registrare uno spazio profondo, attraversato ora da linee rette, ora da prospettive oblique. Gli elementi in scena sono numerosi e stratificati: in una singola inquadratura vive una complessità di gesti, storie, di figure umane in primo piano o sullo sfondo. Mizoguchi seziona l’immagine, la stringe grazie a porte, elementi architettonici o dell’arredo; le esistenze pulsano e scorrono dietro una tenda, in fondo a corridoi, ai margini o al centro dell’inquadratura. Le prostitute appaiono non solo come corpi di consumo, ma ciascuna di esse ha una sua specificità, un momento di gloria dato da un gesto significante, una riga di dialogo struggente o da brevi quanto vivide sottotrame.

I piani sequenza si muovono assecondando la pluralità di vicende umane, l’incrocio di destini: sullo schermo passa la Storia, quieta e dolorosa, fatta di ombre e pianti, mentre un cielo notturno particolarmente opaco (bellissima la fotografia di Miyagawa Kazuo, che predilige un buio grigio e privo di romaticismo) ne è testimone distante e immoto.

English Version

A 1954 film and the last Mizoguchi work to feature Kinuyo Tanaka—who, for the director, embodied a vast gallery of women: geishas, peasants, impoverished wives, betrayed lovers, prostitutes, mothers—each infused with an intense, singular, complex, and chiaroscuro psychological presence. Mizoguchi often confined his female figures within an abstract idealism and a form of martyrdom; but Tanaka was far too intelligent an artist not to escape this imprisonment through the dense, profound, at times mysteriously layered richness of her performances. Hatsuko, the “madam” of The Woman in the Rumor, is likewise a woman of subtly shaded personality. A strict and impeccably controlled manager of an upscale brothel—a family tradition she proudly upholds—Hatsuko knows all too well the torments and unhappiness of love, and secretly nourishes the dream of a “respectable” life and an impossible marriage to a doctor younger than herself. Living in the brothel is Hatsuko’s daughter, Yukiko: an educated, sensitive young woman of elegant, urban appearance (played by Yoshiko Kuga), hostile to her mother’s profession—even though it is precisely that profession which allowed her to complete her studies. Yukiko, too, is a character torn by opposing and irreconcilable forces, caught between the privilege of her position and her disdain for the brothel that is its economic foundation.

In portraying every aspect of these two protagonists with great subtlety—from Hatsuko’s sensual, colorful kimonos and bright smile to Yukiko’s dark, austere outfits and her silent, shadowed demeanor—Mizoguchi places before us two characters who shift and transform before our eyes, at times standing in open opposition to each other, at other times blurring together until their roles nearly exchange. Both in love with the young, opportunistic doctor (another of those vile, mediocre male figures that populate Mizoguchi’s filmography), mother and daughter will find in their shared feeling the key to exposing one another, stripping away every defensive layer, until revealing a core of truth that ultimately brings them to mutual understanding and closeness. The two women thus become part of a single, multifaceted feminine identity: instinctive and maternal, passionate and protective, cynical and innocent all at once. This gradual confrontation—growing ever more intense until it becomes emotionally overwhelming for both the characters and the viewer—unfolds within a spatial setting, the vast and labyrinthine brothel, which Mizoguchi films with a mastery both impenetrable and rarefied. His camera positions itself at a distance to capture deep space traversed at times by straight lines, at times by oblique perspectives. The elements within the frame are numerous and layered: in a single shot lives a complex weave of gestures, stories, and human figures in both foreground and background. Mizoguchi segments the image, tightening it with door frames, architectural details, or pieces of furniture; lives move and pulse behind a curtain, at the end of corridors, at the margins or in the center of the frame. The prostitutes appear not merely as consumable bodies but as distinct individuals, each granted a brief moment of glory—a meaningful gesture, a poignant line of dialogue, or short but vivid subplots of her own.

The long takes glide in harmony with this plurality of human events, this crossing of destinies: history itself passes across the screen—quiet, painful, made of shadows and weeping—while a particularly opaque night sky (Kazuo Miyagawa’s cinematography is beautiful, favoring a gray, unromantic darkness) stands as a distant and unmoving witness.

Scrivi una risposta a A STORY FROM CHIKAMATSU (Chikamatsu Monogatari), 1954, Kenji Mizoguchi – Nubi Fluttuanti Cancella risposta