[Please scroll down for the english version]

A parole il severo signor Hirayama (Shin Saburi) è d’accordo con i giovani del dopoguerra, che non accettano più i matrimoni combinati. Le sue ampie vedute gli consentono di fare da mediatore tra un suo vecchio compagno di scuola, Mikami (Chishū Ryū) e la figlia Fumiko (Yoshiko Kuga), scappata di casa per sfuggire all’autorità paterna. Eppure, Hirayama non è altrettanto comprensivo con Setsuko, sua figlia maggiore, la quale desidera sposarsi con il giovane Masahiko (Keiji Sada). Hirayama nega il permesso, poiché non tollera che la figlia non lo abbia consultato. Si crea allora un’alleanza femminile – fra la Setsuko, la sua amica Yukiko e la moglie apparentemente sottomessa di Hirayama – per favorire il fidanzamento.

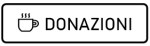

Dopo l’insuccesso di Crepuscolo di Tokyo, troppo cupo per il pubblico, Ozu torna ai temi classici familiari con una sensibilità dolceamara e una levità arricchite dall’uso del colore, che diventa uno strumento narrativo di abbagliante bellezza. Per Fiori d’equinozio, la sua prima opera a colori, il regista preferisce l’Agfacolor al più celebre Eastman color, per la resa del rosso. Noto per la cura maniacale della composizione dell’immagine, adoperò la stessa meticolosità nell’uso del colore; ogni gradazione e ogni accostamento venivano studiati con precisione e disciplina, affinché la palette di ciascuna inquadratura risultasse incredibilmente ricca, varia e artisticamente vibrante. Una tale fioritura coloristica era perfetta per raccontare, in toni leggeri e con grande apertura di pensiero, questa storia di contrasti generazionali e ribellione all’autorità paterna. Ozu ha comprensione e affetto per tutti, padre e figlia, e mai ci offre un ritratto umano che non sia delicato, sfumato e colmo di chiaroscuri. Il rigore dell’inquadratura non fa che mettere in evidenza la turbolenza umana che la abita.

Fiori d’equinozio è tra i lavori più squisitamente stilizzati di Ozu. Le inquadrature sfiorano la pura astrazione: nel dopoguerra è fortissima la volontà del regista di “ricostruire il Giappone” proprio a partire dalle immagini, da un’architettura stilistica che esprima serenità, ordine, bellezza e intensità emotiva, attraverso linee, colori e quadri di vita agiata. E’ all’interno di questo microcosmo armonico che il regista può dar risalto all’oggetto primario del suo cinema, ovvero i sentimenti umani. Non si tratta di escapismo in un’arcadia lontana dalla crisi economica che attanaglia il paese: l’idea di Ozu è quella di “mostrare il fiore di loto nel fango”. Per Ozu la realtà è stratificata e l’intenzione del suo cinema è di mostrarne gli aspetti positivi: anche nel fango può crescere un bellissimo fiore di loto, con il suo trionfo di colori, il suo splendore delicato e la gioia che irradia da tanta bellezza. Ma Fiori d’equinozio è anche un manifesto teorico della sua irriducibile visione: in un decennio in cui il cinema internazionale e anche tanto cinema giapponese cercano il rinnovamento nella novità del Cinemascope, Ozu non si piega al nuovo standard. Rifiutando il formato panoramico (“è come guardare attraverso la buca delle lettere”, afferma), il regista persegue la sua ricerca nel formato 4:3.

Fiori d’equinozio sfrutta la profondità con un senso prospettico di assoluta perfezione classica. Le inquadrature iniziali del matrimonio, o all’interno del vagone del treno, così quelle come di corridoi ed interni sono frutto di uno studio radicale dello spazio, delle linee prospettive e della composizione degli elementi all’interno dell’inquadratura. La bellezza del disegno in profondità e del colore è tale da creare quasi uno stordimento nello spettatore, una sindrome di Stendhal procurata da visioni incantatorie, iniziatiche nella loro matematica regolarità. Tanta stilizzazione non sottrae umanità ai protagonisti, anzi tende a metterla in risalto: è il palcoscenico di un “disordine” di emozioni e sentimenti.

Pur guardando con nostalgia alle tradizioni (si veda il canto di Ryū Chishū ), il regista riserva una profonda simpatia ai personaggi più giovani e ci mostra coppie volitive quanto responsabili, decise a coronare i propri sogni amorosi lavorando duramente senza ingerenze familiari. Una visione rappresentata dalla frase “trasformare l’acciaio in oro”: la felicità, come in Tarda Primavera, è una conquista e un lavoro quotidiano.

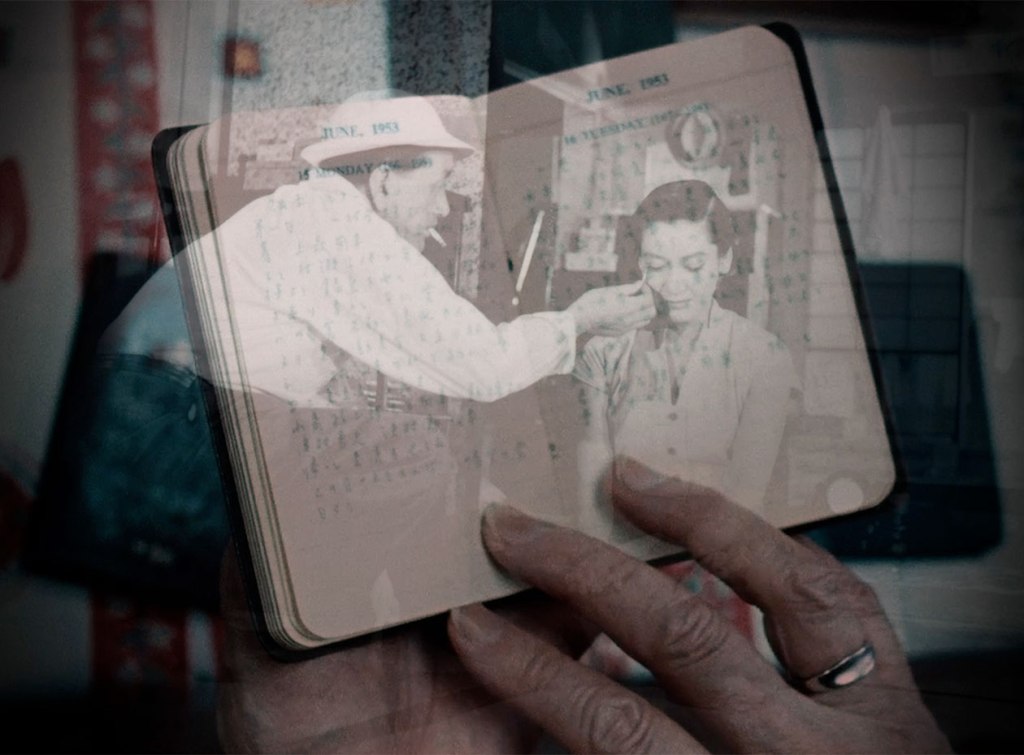

Gli aspetti deteriori della tradizione emergono nel destino del personaggio di Kinuyo Tanaka, madre sottomessa agli umori di un marito non passionale e testardo, in un matrimonio combinato e trascorso tra abitudini e solitudine; una donna obbediente, spesso costretta a reprimere il proprio pensiero e la propria volontà, o a mascherarli in un sorriso educato. Ozu ci mostra la forza paziente e addolorata di un personaggio apparentemente tanto passivo: in realtà, lei è la chiave dell’armonia familiare. Nelle bellissime inquadrature di Tanaka si racchiude un’immagine di straordinaria forza commovente e sentimentale.

English Version

In words, the stern Mr. Hirayama (Shin Saburi) agrees with the young people of the postwar years, who no longer accept arranged marriages. His broad-minded views allow him to mediate between an old schoolmate, Mikami (Chishū Ryū), and Mikami’s daughter Fumiko (Yoshiko Kuga), who has run away from home to escape her father’s authority. Yet Hirayama is far less understanding toward Setsuko, his eldest daughter, who wishes to marry the young Masahiko (Keiji Sada). Hirayama denies them his permission, unable to tolerate the fact that his daughter did not consult him first. This gives rise to a small female alliance—between Setsuko, her friend Yukiko, and Hirayama’s seemingly submissive wife—aimed at supporting the engagement.

After the failure of Tokyo Twilight, deemed too bleak by audiences, Ozu returns to his classic family themes with a bittersweet sensitivity and a newfound lightness enriched by the use of color, which becomes a narrative vehicle of dazzling beauty. For Equinox Flower, his first color film, the director chooses Agfacolor over the more celebrated Eastmancolor for the rendering of red. Known for his near-manic care in composing images, he brought the same meticulousness to the use of color: every shade and every juxtaposition was studied with precision and discipline so that the palette of each shot would be incredibly rich, varied, and artistically vibrant. Such a chromatic blossoming was perfect for recounting, in a light tone and with great openness of thought, this story of generational contrasts and rebellion against paternal authority. Ozu shows understanding and affection for everyone, father and daughter alike, and he never offers us a human portrait that is anything less than delicate, nuanced, and full of chiaroscuro. The rigor of the framing only highlights the human turbulence that inhabits it.

Equinox Flower is among Ozu’s most exquisitely stylized works. The shots verge on pure abstraction: in the postwar years, the director expresses a strong desire to “rebuild Japan” starting from images themselves—from a stylistic architecture that conveys serenity, order, beauty, and emotional intensity through lines, colors, and scenes of comfortable domestic life. Within this harmonious microcosm, he is able to give prominence to the primary object of his cinema: human feelings. This is not escapism into an arcadia removed from the economic crisis afflicting the country; Ozu’s idea is to “show the lotus flower in the mud.” For Ozu, reality is layered, and the intention of his cinema is to reveal its positive aspects: even in the mud, a beautiful lotus flower can grow, with its triumph of colors, its delicate radiance, and the joy emanating from such beauty. But Equinox Flower is also a theoretical manifesto of his irreducible vision: in a decade when international cinema—and much Japanese cinema as well—sought renewal in the novelty of Cinemascope, Ozu refused to bend to the new standard. Rejecting the widescreen format (“it is like looking through a mail slot,” he said), the director continued his artistic exploration within the 4:3 frame.

Equinox Flower employs depth with an absolutely classical sense of perspective. The opening shots at the wedding, the images inside the train carriage, and those set in corridors and domestic interiors all arise from a radical study of space, of perspective lines, and of the placement of elements within the frame. The beauty of the depth composition and of the color is such that it produces a kind of visual intoxication, a Stendhal syndrome brought on by enchanting, almost initiatory visions, mathematical in their regularity. Such stylization does not diminish the humanity of the characters; on the contrary, it serves to highlight it: this is the stage on which a “disorder” of emotions and feelings unfolds. While Ozu looks nostalgically to tradition (as in Chishū Ryū’s song), he also shows profound sympathy for the younger characters, presenting couples who are strong-willed yet responsible, determined to fulfill their romantic dreams by working hard and without familial interference. Their worldview is encapsulated in the phrase “turning steel into gold”: happiness, as in Late Spring, is something to be earned through daily effort.

The darker aspects of tradition emerge in the fate of the character played by Kinuyo Tanaka, a mother subdued by the moods of an unpassionate, stubborn husband, bound within an arranged marriage spent amid routines and solitude. She is an obedient woman, often forced to repress her own thoughts and will—or to mask them with a polite smile. Ozu shows us the patient, sorrowful strength of a character who seems passive: in truth, she is the key to the family’s harmony. In the film’s beautiful shots of Tanaka resides an image of extraordinary emotional and sentimental power.

Scrivi una risposta a TARDO AUTUNNO (Akibiyori, 1960), Yasujirō Ozu – Nubi Fluttuanti Cancella risposta