[Please scroll down for the English version]

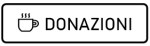

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Fukazawa Shichirō, The Ballad of Narayama racconta una leggenda tradizionale mediante forme cinematografiche inedite e sperimentali, ispirate al teatro classico giapponese. Il sensibile umanesimo di Kinoshita affiora tra straordinari tecnicismi, confermando la capacità del regista nell’offrire uno sguardo “totale” sul proprio paese, tra arte, sociologia e storia.

In un villaggio di montagna, dove il cibo scarseggia e la sopravvivenza è ardua, la tradizione impone che al compimento dei settant’anni gli anziani vengano portati sulla cima del Monte Nara e lasciati lì a morire. L’anziana sacrificale al centro del racconto è Orin, una donna semplice che trascorre i suoi giorni lavorando nella risaia e preoccupandosi per le sorti della famiglia. Suo figlio Tatsuhei non sopporta l’idea di perderla, ma Orin è decisa a compiere il pellegrinaggio finale.

In un’intervista a «Kinema Junpō», a proposito della sua straordinaria prolificità, Kinoshita dichiarò: «Non posso farci nulla… Le idee per i film mi piombano in testa come palline di carta in un cestino».

Se si pensa a ciò che Kinoshita è riuscito a realizzare e sperimentare nell’arco della sua carriera, non si può che restare stupiti. La sua passione per le “forme possibili” del cinema lo ha portato a riflettere sui codici dei generi, esplorarli e modificarli. Da un iniziale realismo, Kinoshita si è via via addentrato in un percorso di originalità ed audacia espressiva: ha usato il colore per primo, enfatizzandone il valore astratto e metaforico; ha trasformato i tratti più severi e crudeli di storia e società in poesia, attraverso l’uso di mascherini che trasfigurassero la sofferenza e il passato; ha inclinato la macchina da presa ottenendo angoli olandesi in cui tradurre lo smarrimento e la diversità dei personaggi rispetto al contesto. In tutta la sua propensione irrefrenabile nei confronti delle immagini e del loro potere, Kinoshita ha anticipato le rivoluzioni degli anni ’60, i postmodernismi, la disgregazione del racconto cronologico in frammenti onirici, flashback e tempo interiore. Artista totale novecentesco, Kinoshita ha anche studiato con serietà il rapporto tra immagine e colonna sonora, integrandole in narrazioni sinestetiche e complesse.

The Ballad of Narayama rappresenta forse il momento di maggior sperimentazione e meraviglia stilistica nell’arco di una carriera contraddistinta dall’eccezionalità: un film che nella brevità dei suoi 98 minuti fonde storia e futuro, tradizione e avanguardia. Il regista aderisce agli stilemi del teatro kabuki senza tradirli: li trasforma in linguaggio cinematografico di grande raffinatezza, ma accessibile in senso popolare. Introdotto dal kuroko, il tradizionale macchinista teatrale incappucciato e vestito di nero, il film “apre il sipario” sulla leggenda e mette immediatamente a nudo i meccanismi della finzione. (1).

Riprendendo la tradizione crudele dell’Obasute – ovvero l’abbandono degli anziani alla morte, in una società che rifiutava di occuparsi di loro – Kinoshita mette in scena la freddezza universale e senza tempo che circonda la vecchiaia. La distopia del recente Plan 75 (2022, Chie Hayakawa , metafora del contemporaneo Giappone invecchiato e suicida, non fa che rendere The Ballad of Narayama ancora attuale: l’idea di “sbarazzarsi” degli anziani, come convenzione sociale comunemente accettata e prosciugata di qualsiasi obiezione morale o emotiva, continua a sopravvivere (2).

In passato questo atteggiamento assunse addirittura una dimensione rituale, ed è proprio la sistematizzazione in folklore e leggenda a risaltare nell’allestimento antinaturalistico del regista.

Kinoshita pone al centro dell’opera la disumanità della pratica, omettendo esplicite sbavature sentimentali. La sua abilità nel mantenere una distanza, concentrandosi sul rigore formale del Kabuki, paradossalmente genera un’altissima tensione emotiva. Il regista giunge alle pendici più estreme del suo percorso all’interno della società giapponese, rivelando, attraverso la trasfigurazione dell’arte, la pulsione di morte innescata nel singolo individuo. Orin (la straordinaria Kinuyo Tanaka), ancora sana e dedita alacremente al lavoro, teme lo scherno della comunità: giunge persino a distruggersi i denti con una pietra (3), per assecondare gli stereotipi sulla vecchiaia. Nel pellegrinaggio a Narayama, desiderato con orgoglio e determinazione, intravede un disegno divino ed un dovere morale.

Viaggio esperienziale verso il nulla, il film allestisce uno spettacolo tanto più colmo di vita e variopinto – con sipari che si aprono, fondali che scompaiono, trucchi, albe e tramonti in successione, campi dorati e lune misteriose (4,5,6) – quanto più si avvicina alla morte, fino alla desolazione funebre e spirituale di Narayama. Kinoshita trasforma l’archetipo teatrale in cinema totale e fiammeggiante, in un trionfo di finzione e technicolor, non dissimile da Il Mago di Oz (1939, Victor Fleming): un’esperienza di pura meraviglia, filosofica ed estatica, realizzata con un’audacia tecnica e sperimentale sorprendenti.

Bellissime le uscite di scena dei personaggi, che “scorrono” lateralmente mentre la luce si spegne su di loro, imitando i cambi di scenografia tramite palcoscenico rotante (mawari butai): uno dei tanti espedienti tecnici cui ricorre Kinoshita per trasformare lo spazio teatrale in libertà cinematografica (7).

Il regista lavora sulla profondità di campo, stratifica l’immagine mediante “quinte” teatrali, si serve di fondali che scorrono rapidi, a esprimere la sorpresa o l’emozione dei protagonisti. Gli stati d’animo cambiano assieme ai colori; tutto è magnifico e intenso, per confondere la bellezza del vivere col dolore della morte. Sono presenti, com’è tipico dello stile del regista, molti carrelli orizzontali, quasi a ricordare, come disse Jean Cocteau, che la vita è una caduta orizzontale.

Spesso Kinoshita ricorre ad ampi movimenti a 360°, per mostrare gli artifici del set; altre volte invece predilige immagini statiche e frontali, la cui astrazione scompone lo spazio in forme geometriche. Straordinario l’uso della luce, che talvolta funge da mascherino per isolare i protagonisti e concentrare su di loro l’attenzione degli spettatori.

Kinoshita riserva i primi piani all’enfatizzazione di emozioni primarie, mentre il campo medio è lo strumento d’elezione per un’osservazione capillare del destino dei protagonisti. C’è una cura meticolosa nella collocazione del personaggio nello spazio che li circonda: la Natura, rigogliosa ed espressiva, fa da controcanto ai paesaggi interiori. Così visibilmente falso e ricostruito in studio, il contesto amplifica con la sua stilizzata perfezione la transitorietà dell’esperienza umana: si pensi alla bellezza di alberi e fiori primaverili, ma anche alla presenza minacciosa di corvi, nebbia e roccia arida della montagna invernale. Giunti alla montagna della morte, si spalanca ai nostri occhi una scenografia orrorifica e poetica, tra atmosfere indistinte, cielo plumbeo e scheletri raccapriccianti (8, 9): una visione simile a quella che Lucio Fulci, più di 20 anni dopo, allestirà nel finale di E tu vivrai nel terrore… L’aldilà (1981).

Come spesso accade nel cinema di Kinoshita, dolore e sofferenza vengono ingoiati dal Tempo, metaforizzato dal passaggio del treno nella sequenza finale, mentre il fascino della leggenda si insedia per sempre nell’immaginario. Nel 1983 Imamura gira una nuova versione più scabra e realista, vincendo la Palma d’Oro a Cannes; ma anche il cinema contemporaneo non riesce a sottrarsi al suo retaggio, come dimostra il recente Come in Irene (2018) di Keisuke Yoshida, che offre una inedita versione “al femminile” del viaggio finale sotto la neve (10).

© Riproduzione riservata

[Articolo originariamente apparso su Sonatine]

English Version

Based on the novel of the same name by Fukazawa Shichirō, The Ballad of Narayama tells a traditional story through innovative and experimental cinematic forms, inspired by classical Japanese theater. Kinoshita’s sensitive humanism emerges amidst extraordinary technicality, confirming the director’s ability to offer a comprehensive view of his country, encompassing art, sociology, and history.

In a mountain village, where food is scarce and survival is difficult, tradition dictates that upon reaching seventy, the elderly be taken to the summit of Mount Nara and left there to die. The sacrificial old woman at the center of the story is Orin, a simple woman who spends her days working in the rice paddy and worrying about her family’s fate. Her son Tatsuhei cannot bear the thought of losing her, but Orin is determined to make the final pilgrimage.

In an interview with “Kinema Junpō,” regarding his extraordinary prolificacy, Kinoshita stated: “I can’t help it… Ideas for films fall into my head like paper balls in a basket.”

When you consider what Kinoshita achieved and experimented with throughout his career, you can’t help but be amazed. His passion for the “possibilites” of cinema led him to reflect on, explore, and modify genre codes. From an initial realism, Kinoshita gradually embarked on a path of originality and expressive boldness: he was the first to use color, emphasizing its abstract and metaphorical value; he transformed the harshest and cruelest traits of history and society into poetry, through the use of mattes that transfigured suffering and the past; he tilted the camera, creating Dutch angles that conveyed the characters’ bewilderment and difference from their context. In all his irrepressible fascination with images and their power, Kinoshita anticipated the revolutions of the 1960s, postmodernism, and the disintegration of chronological narrative into dreamlike fragments, flashbacks, and stream of consciousness. Kinoshita also rigorously studied the relationship between image and soundtrack, integrating them into complex, synesthetic narratives.

The Ballad of Narayama represents perhaps the moment of greatest stylistic experimentation and wonder in a career marked by exceptionality: a film that, within its brevity of 98 minutes, blends history and future, tradition and avant-garde. The director adheres to the stylistic features of kabuki theater without betraying them: he transforms them into a cinematic language of great refinement, yet accessible in a popular sense. Introduced by the kuroko, the traditional hooded and black-clad stagehand, the film “raises the curtain” on the legend and immediately lays bare the mechanisms of fiction. (1).

Reviving the cruel tradition of Obasute—the abandonment of the elderly to death in a society that refused to care for them—Kinoshita stages the universal and timeless coldness surrounding old age. The dystopia of Chie Hayakawa’s recent Plan 75 (2022), a metaphor for contemporary aging and suicidal Japan, only makes The Ballad of Narayama relevant again: the idea of “getting rid” of the elderly, as a commonly accepted social convention, devoid of any moral or emotional objection, continues to survive (2).

In the past, this attitude even took on a ritualistic dimension, and it is precisely this systematization in folklore and legend that stands out in the director’s anti-naturalistic staging.

Kinoshita places the inhumanity of the practice at the center of the work, omitting explicit sentimental overtones. His ability to maintain a distance, focusing on the formal rigor of Kabuki, paradoxically generates a very high emotional tension. Orin, still healthy and busily dedicated to her work, fears the community’s ridicule: she even goes so far as to destroy her teeth with a stone (3), to comply with stereotypes about old age. In the pilgrimage to Narayama, desired with pride and determination, she glimpses a divine plan and a moral duty.

An experiential journey to “nowhere”, the film creates a spectacle that becomes more vibrant and colorful—with curtains that open, backdrops that disappear, tricks, successive sunrises and sunsets, golden fields, and mysterious moons (4, 5, 6)—the closer it gets to death, right up to Narayama’s funereal and spiritual desolation. Kinoshita transforms the theatrical archetype into total and flamboyant cinema, in a triumph of fiction and technicolor, not unlike The Wizard of Oz (1939, Victor Fleming): an experience of pure wonder, philosophical and ecstatic, crafted with surprising technical and experimental boldness.

The characters’ exits are beautiful, “sliding” sideways as the lights fade on them, imitating the changes in scenery via a rotating stage (mawari butai): one of the many technical devices Kinoshita uses to transform theatrical space into cinematic freedom (7).

The director works on deep focus, layering the image and using rapidly flowing backdrops to express the protagonists’ surprise or emotion. Moods change along with the colors; everything is magnificent and intense, to confuse the beauty of living with the pain of death. As is typical of the director’s style, there are many horizontal tracking shots, almost as if to remind us, as Jean Cocteau said, that life is a horizontal fall.

Kinoshita often uses sweeping 360° movements to reveal the artifices of the set; at other times, he favors static, frontal images, whose abstraction breaks down space into geometric shapes. His use of light is extraordinary.

Kinoshita reserves close-ups for emphasizing primary emotions, while the medium shot is the preferred choice for a detailed observation of the protagonists’ fates. Meticulous care is taken in positioning the characters in the space around them: nature, lush and expressive, provides a counterpoint to the interior landscapes. Thus visibly fake and studio-reconstructed, the context amplifies, with its stylized perfection, the transience of human experience: think of the beauty of spring trees and flowers, but also of the menacing presence of crows, fog, and the barren rock of the winter mountain. Upon reaching the mountain of death, a horrific and poetic scene opens up before our eyes, with its hazy atmosphere, leaden skies, and terrifying skeletons (8, 9): a vision similar to the one Lucio Fulci, more than 20 years later, would create in the finale of The Beyond (1981).

As often happens in Kinoshita’s cinema, pain and suffering are swallowed up by Time, metaphorized by the passing of the train in the final sequence, while the allure of the legend takes root forever in the imagination. In 1983, Imamura shot a new, harsher and more realistic version, winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes; But even contemporary cinema cannot escape its legacy, as demonstrated by Keisuke Yoshida’s recent Come on Irene (2018), which offers an unprecedented version of the final journey under the snow (10).

Lascia un commento