[Please scroll down for the English version]

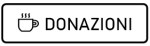

Kikunosuke Onoue, figlio adottivo di un importante attore, scopre di essere elogiato per la sua mediocre recitazione solo perché è l’erede del padre. L’unica persona che gli parla sinceramente del suo talento è la balia Otoku. Tra i due nasce un sentimento che causa il licenziamento della ragazza. Indignato, Kiku lascia la casa familiare e per lunghi anni si unisce a una compagnia itinerante mentre Otoku si sacrifica per il suo successo.

Primo e unico film sopravvissuto di una trilogia realizzata da Mizoguchi sul teatro del periodo Meiji, The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums è rimasto per molto tempo inedito in Occidente. Opera lunga e complessa, il film esprime compiutamente e con grande raffinatezza la peculiare visione di cinema di Mizoguchi, imperniata su un elaborato montaggio interno all’inquadratura. I lunghi piani sequenza strutturano il film secondo il principio “un’unica inquadratura/una scena”; l’esteso minutaggio (143 minuti) asseconda una concezione temporale basata sull’importanza del gesto naturale, delle emozioni umane associate alla durata e quindi descritte in ogni sfumatura.

Tratto da un’opera teatrale shinpa, The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums è un oggetto artistico a cavallo tra finzione e realtà. La visione deterministica, la descrizione oggettiva della realtà sociale rigidamente gerarchica dell’epoca si sposano a una rigorosa architettura strutturale e una tensione narrativa e simbolica; ed è in questo intrecciarsi di vita e rappresentazione che risiede la maestria di Mizoguchi. La tragedia di Otoku, la dolente protagonista femminile, aderisce fedelmente ai codici del dramma teatrale popolare: Mizoguchi enfatizza l’aspetto finzionale con una mise en scène che predilige l’irrealtà di esterni visibilmente ricostruiti, luci teatrali, notti argentee e spirituali, mentre la colonna sonora accompagna le sofferenze della protagonista con i tipici strumenti a percussione del kabuki. In altri momenti, invece, prevale l’approccio realistico: si veda l’attenta riproduzione dei labirintici spazi del teatro, mediante un sofisticato montaggio interno che separa il palcoscenico, le quinte, e il sotterraneo dove Otoku prega per il successo di Kikunosuke; oppure lo sguardo oggettivo sulla brutale esistenza degli attori itineranti, costretti a vivere di stenti e inaspriti dalle difficoltà.

Particolarmente emblematica la scena in cui, dopo una serie di insuccessi, la compagnia ambulante viene sostituita da uno spettacolo di sumō femminile. Durante lo sgombero del misero teatro, Mizoguchi “rompe” la fissità della macchina da presa con un inaspettato movimento di macchina sulla pioggia battente fuori dalla finestra: un fuori campo su ostili elementi naturali a cui ci viene dato accesso. La lotta per la sopravvivenza appare ancora più intensa attraverso gli aspetti sensoriali – il freddo, la rigida umidità invernale, la fame – che il regista ci lascia percepire.

Ma la scena che rimane più impressa nella memoria per l’inedita costruzione formale è la sequenza del primo dialogo tra Otoku e Kikunosuke, attraverso una lenta carrellata laterale dal basso della durata di oltre quattro minuti. In questo lungo movimento orizzontale assistiamo alla nascita di un sentimento e alla definizione dei due caratteri. Kiku si appassiona alla sincerità della ragazza, gentile e protettiva, ma anche dotata di una comprensione innata e spontanea dell’arte teatrale. Con i suoi cambi di prospettiva, l’elaborato piano sequenza ci trasmette le esitazioni di Kiku, la presa di coscienza, la seduzione che su di lui esercitano le parole di Otoku, creatura di luminosa, ingenua purezza. Lo scorrere del tempo accresce le emozioni dei personaggi come degli spettatori, partecipi di ogni sfumatura sensibile che affiora nella voce e nei gesti della coppia.

Una caratteristica della rappresentazione di Otoku è la sua espressività attraverso la luce: spesso la vediamo immersa nell’ombra, ridotta a una semplice silhouette; altre volte la luce la colpisce di taglio, quasi ferendola. Otoku è una donna “senza volto”, invisibile e destinata a una fine amara. La macchina da presa la inquadra non solo in lontananza e a figura intera, secondo un procedimento caro a Mizoguchi, ma prevalentemente di spalle o al buio. Il suo viso non è orientato verso l’obiettivo; Otoku è un personaggio umile e “votato alla sparizione”, che nella postura riflette la coscienza della propria classe sociale.

In un mondo maschile – nella vita come sul palcoscenico – Otoku resta nei recessi, in quell’ombra in cui Mizoguchi la situa sin dall’inizio. Con il suo estremo sacrificio per Kiku e la serena rinuncia a sé, Otoku è tra i più emblematici personaggi femminili del regista, imprigionata in un’aura di idealismo che la inchioda alla propria condizione.

Il romanticismo, che pure è presente in The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, non raggiunge le vette del sublime A story from Chikamatsu (1954) perché in realtà qui non ci troviamo di fronte alla storia di una coppia, ma di due entità “separate” e dotate non solo di diverso status ma di un diverso sentire. L’amore, per Kiku, è una forza che rassicura e offre egoistica stabilità al proprio narcisismo; mentre per Otoku è un martirio, un atto di fede nell’altro. Nelle sequenze dello spettacolo teatrale a Nagoya, quando Kiku trionfa interpretando con grande delicatezza il ruolo onnagata di Sumizome, Mizoguchi lo inquadra dietro finissimi tendaggi: l’artista è separato dal resto del mondo, isolato nella propria sensibilità.

The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum è soprattutto un film/manifesto sull’atto del vedere: ogni composizione dell’immagine prevede un osservatore, che sia un servo dietro uno shōji, un passante, un familiare, o il pubblico seduto in platea; ma vi è anche, fortissima, la presenza di uno sguardo dall’alto (mediante uso frequente del dolly), che parla di una predestinazione, o un destino osservato da divinità indifferenti.

English version

Kikunosuke Onoue, the adopted son of a prominent actor, discovers that he’s being praised for his mediocre acting simply because he’s his father’s heir. The only person who sincerely speaks to him about his talent is his nanny, Otoku. A feeling develops between the two, resulting in the girl’s dismissal. Outraged, Kiku leaves the family home and spends many years joining a traveling troupe, while Otoku sacrifices himself for his success.

The first and only surviving film of a trilogy Mizoguchi made about Meiji-era theater, The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums remained unreleased in the West for a long time. A long and complex work, the film fully and with great sophistication expresses Mizoguchi’s distinctive cinematic vision, centered on elaborate in-frame editing. Long sequence shots structure the film according to the “one shot/one scene” principle; The extended running time (143 minutes) supports a conception of time based on the importance of natural gestures, of human emotions associated with duration and therefore described in every nuance.

Adapted from a Shinpa play, The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums is an artistic object straddling fiction and reality. The deterministic vision and objective description of the rigidly hierarchical social reality of the time are combined with rigorous structural architecture and narrative and symbolic tension; and it is in this intertwining of life and representation that Mizoguchi’s mastery lies. The tragedy of Otoku, the suffering female protagonist, faithfully adheres to the codes of popular theater drama: Mizoguchi emphasizes the fictional aspect with a mise en scène that favors the unreality of visibly reconstructed exteriors, theatrical lighting, and silvery, spiritual nights, while the soundtrack accompanies the protagonist’s suffering with typical kabuki percussion instruments. In other moments, however, a realistic approach prevails: see the careful reproduction of the theater’s labyrinthine spaces, through a sophisticated internal editing that separates the stage, the wings, and the basement where Otoku prays for Kikunosuke’s success; or the objective look at the brutal existence of traveling actors, forced to live in hardship and embittered by hardship.

Particularly emblematic is the scene in which, after a series of failures, the traveling troupe is replaced by a female sumo show. During the evacuation of the shabby theater, Mizoguchi “breaks” the camera’s fixity with an unexpected panning shot of the pouring rain outside the window: an off-screen view of hostile natural elements to which we are given access. The struggle for survival appears even more intense through the sensorial aspects—the cold, the harsh winter humidity, the hunger—that the director allows us to perceive.

But the scene that remains most memorable for its original formal construction is the sequence of the first dialogue between Otoku and Kikunosuke, a slow lateral tracking shot from below lasting over four minutes. In this long horizontal movement, we witness the birth of a feeling and the definition of the two characters. Kiku is captivated by the girl’s sincerity, kind and protective, but also endowed with an innate and spontaneous understanding of the art of theater. With its shifts in perspective, the elaborate long take conveys Kiku’s hesitations, his realization, and the seduction he feels through the words of Otoku, a creature of luminous, naive purity. The passage of time heightens the emotions of the characters and spectators alike, participating in every sensitive nuance that emerges in the couple’s voices and gestures.

A hallmark of Otoku’s portrayal is her expressiveness through light: often we see her immersed in shadow, reduced to a mere silhouette; other times the light strikes her sharply, almost wounding her. Otoku is a “faceless” woman, invisible and destined for a bitter end. The camera frames her not only from the distance, following a technique dear to Mizoguchi, but mainly from behind or in the dark. Her face is not oriented toward the lens; Otoku is a humble character, “destined to disappear,” whose posture reflects her social class consciousness.

In a male world—in life as on stage—Otoku remains in the recesses, in that shadow where Mizoguchi places her from the beginning. With her ultimate sacrifice for Kiku and her serene self-denial, Otoku is among the director’s most emblematic female characters, imprisoned in an aura of idealism that nails her to her condition.

Romanticism, which is also present in The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, does not reach the heights of the sublime A Story from Chikamatsu (1954) because here we are not faced with the story of a couple, but of two “separate” entities who have not only different statuses but also different feelings. Love, for Kiku, is a force that reassures and offers selfish stability to his own narcissism; while for Otoku, it is a martyrdom, an act of faith in the other. In the sequences of the theatrical performance in Nagoya, when Kiku triumphs with his masterful interpretation of the onnagata role of Sumizome, Mizoguchi frames him behind exquisite drapes: the artist is separated from the rest of the world, isolated in his own sensibility.

The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum is above all a film/manifesto about the act of seeing: each composition of the image foresees an observer, whether a servant behind a shōji, a passerby, a family member, or the audience seated in the stalls; but there is also a very strong presence from above (through frequent use of dolly shots), which speaks of a predestination, or a destiny observed by indifferent deities.

Scrivi una risposta a Shiguéhiko Hasumi: Another History of the Movie in America and Japan. Le scelte del grande critico per “un’altra storia del cinema”. – Nubi Fluttuanti Cancella risposta