[Please scroll down for the English version]

Nel 1997 Kon Satoshi esordisce sul grande schermo con Perfect Blue, dando una forte scossa all’industria anime: artisti e critici rimasero impressionati da questo debutto audace, in cui filosofie novecentesche, psicanalisi e nouveau roman, metacinema e gusto horror allo stesso tempo raffinato e exploitation aderivano senza soluzione di continuità. Dalla radicata passione cinefila di Kon, dal suo immaginario liberamente in movimento tra realtà e sogno, era nata un’opera che mirava a riprodurre lo spirito dell’essere umano e il suo discorso interiore. Il film, purtroppo, non ebbe successo commerciale, cosa che pose Kon su un piano scomodo: la sua reazione fu di tentare con una secondo lungometraggio meno radicalmente “di genere”, ma che non tradisse la sua ispirazione.

Da questo stato d’animo ha origine Millennium Actress, tra i più bei film “sul cinema” mai realizzati. Per la sua complessità, per il suo linguaggio “generativo” che innesca continui rimandi metacinematografici, per la qualità compositiva che affonda in un immaginario collettivo profondo, Millennium Actress è un’opera “sorella” di altri due misterici capolavori: Viale del Tramonto (1950) e Fedora (1978), forme di espressione artistica che superano il proprio tempo per diventare frammenti di percorso iniziatico attraverso lo spazio surrealista del cinema, il suo potere veggente, la sua natura psicanalitica.

Tra tutti i film di Kon, Millennium Actress è forse quello che più intensamente guarda al passato, o ancor meglio alle relazioni che intercorrono tra passato, presente e futuro. Venato di malinconia, ma anche di amore per la vita e le sue infinite possibilità, l’opera esplora il mistero della circolarità del tempo: il passato proietta luci e ombre sul presente, mentre il futuro è quel viso che si mostra e fugge, lasciandoci col desiderio di raggiungerlo.

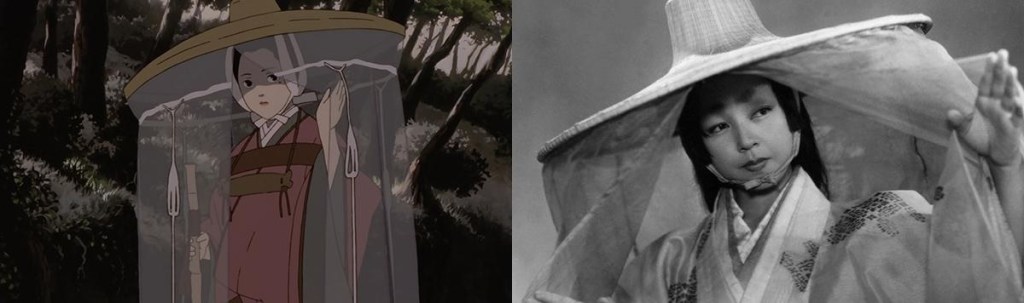

Apparentemente la trama è semplice: un documentarista si reca a intervistare la celebre ed elusiva diva Fujiwara Chiyoko, ritirata da trent’anni in un solitario isolamento. Come tutte le eroine di Kon, Chiyoko è una figura “duplice” in cui il regista trasferisce i tratti biografici e il percorso artistico di due grandi protagoniste del cinema giapponese: Hara Setsuko Hara e Hideko Takamine. Flashbacks ci conducono dolcemente (à la Cocteau) nel passato di Chiyoko, mostrandoci la sua carriera di attrice e la sua parallela ricerca di un uomo misterioso, di cui è perdutamente innamorata. Durante l’intervista, il documentarista e il suo cameraman “scivolano” all’interno dei ricordi di Chiyoko, prendendone parte: ecco allora che la grande avventura del cinema giapponese diviene anche racconto individuale, memoria e sogno.

Seguendo la linea tracciata da Perfect Blue, opera speculare, Kon ci suggerisce che l’immagine cinematografica non può restituire la “realtà oggettiva”, poiché questa non esiste; anzi, il suo specifico è la restituzione di molteplici realtà soggettive. Nel cuore umano “i ricordi, il presente, il passato e il futuro coesistono”, secondo la filosofia di Kon; la vita passa attraverso la libertà e la fantasia delle nostre percezioni.

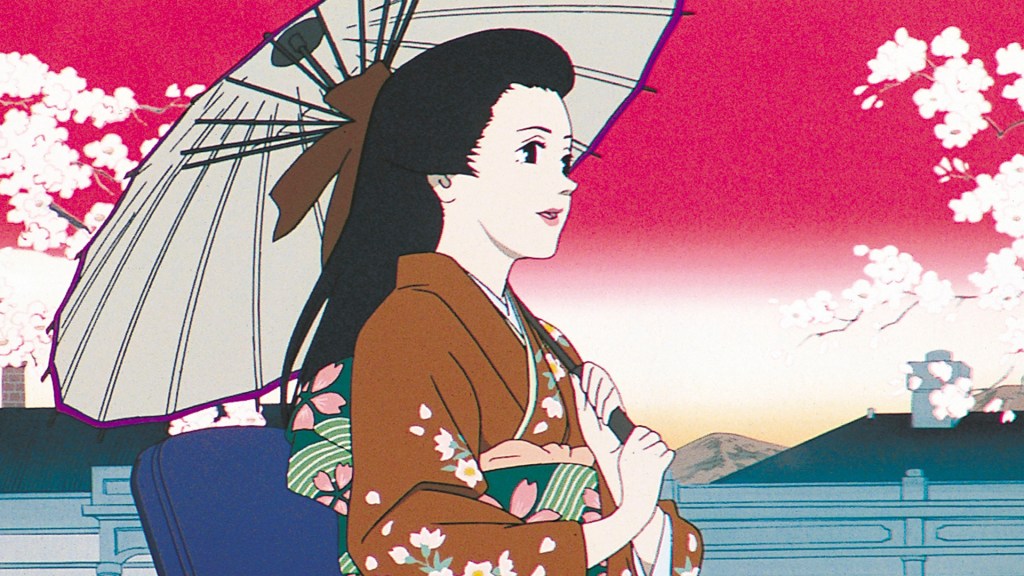

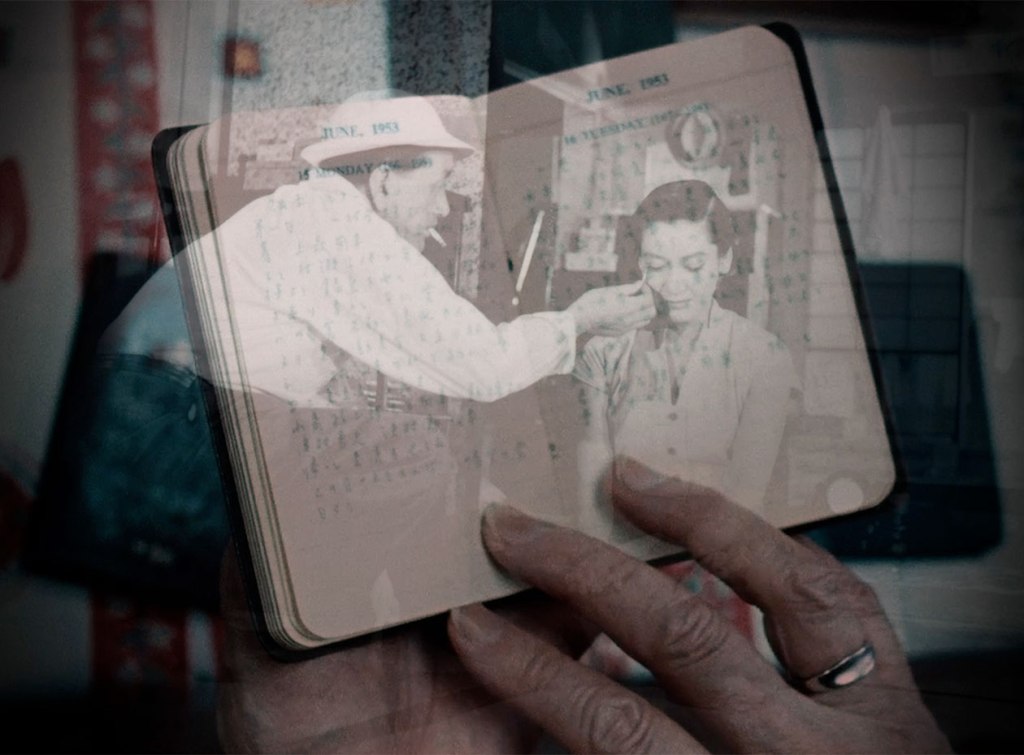

La troupe segue Chiyoko attraverso diversi periodi temporali e generi che fanno riferimento a grandi autori del passato (Ozu, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, Naruse…): vere lettere d’amore tecnicamente stupefacenti. La protagonista corre nel mezzo di una realtà “messa in scena” in cui i fondali colorati cambiano come in un film di Kinoshita; piani sequenza si risolvono in una concezione temporale soggettiva, che vede anni trascorrere in un secondo; piogge di frecce diventano bombe, scenografie jidai-geki si trasformano in paesaggi devastati dalla seconda guerra mondiale; manifesti cinematografici (What’s Your Name e Love Letter, entrambi del 1953) ci parlano di realismo e romanticismo post-bellici. La memoria del cinema è un nastro che scorre senza fine. Chiyoko, modellata su Setsuko Hara, Hideko Takamine ma anche Kinuyo Tanaka, è “la donna” del cinema giapponese: creatura trasfigurata, amata, desiderata; personaggio protagonista del cambiamento, corpo del sacrificio, ma sempre pronta a vivere e amare, a gettarsi in un futuro sconosciuto. La Millennium Actress piange con il viso tra le mani ricordandoci la Noriko di Viaggio a Tokyo (1953), corre in bicicletta come Hisako in Twenty-four eyes (1954), affronta una photocall giornalistica assieme a Godzilla (1954), cammina tra le macerie come Yukiko di Floating Clouds (1955)

Stupisce, ancora una volta, l’ingegno senza fine del regista nel sovrapporre in forme emotivamente struggenti realtà e finzione, e parallelamente cinema e metacinema. Kon interpreta codici linguistici in trasformazione: la pulizia classica diviene immagine “instabile” moderna fino ad arrivare alle sperimentazioni del fantastico. La colonna sonora di Susumu Hirasawa, che si sviluppa attraverso stili differenti (dal pianoforte romantico all’inquietudine elettronica) contribuisce a proiettare il film in una dimensione irraggiungibile: là dove Chiyoko, incurante degli ostacoli, è la forte/fragile viaggiatrice dell’Amore: “dopotutto… è rincorrerlo la cosa che mi piace di più”.

© Riproduzione riservata

English Version

In 1997, Satoshi Kon made his feature debut with Perfect Blue, shaking the anime industry to its core. Artists and critics alike were struck by this daring first film, in which twentieth-century philosophies, psychoanalysis, and the nouveau roman blended seamlessly with metacinema and a horror sensibility that was at once refined and exploitative. Born from Kon’s deep cinephilia and his imagination freely moving between dream and reality, the film sought to reproduce the spirit of the human being and the texture of inner discourse. Unfortunately, it was not a commercial success — a setback that placed Kon in an uncomfortable position. His response was to attempt a second feature that was less radically “genre,” yet true to his inspiration.

Out of this state of mind came Millennium Actress, one of the most beautiful films about cinema ever made. For its complexity, its “generative” language filled with metacinematic echoes, and its compositional richness rooted in a deep collective imagery, Millennium Actress stands as a “sister work” to two other mysterious masterpieces: Sunset Boulevard (1950) and Fedora (1978). These are forms of artistic expression that transcend their time to become fragments of an initiatory journey through the surrealist space of cinema — its visionary power, its psychoanalytic nature.

Among all Kon’s works, Millennium Actress is perhaps the one that looks most intently to the past — or rather, to the relationships between past, present, and future. Tinged with melancholy yet filled with love for life and its infinite possibilities, the film explores the mystery of time’s circularity: the past casts its light and shadows upon the present, while the future is that elusive face — appearing and vanishing — that leaves us longing to reach it.

On the surface, the plot seems simple: a documentary filmmaker visits the famous and elusive actress Chiyoko Fujiwara, who has lived in solitude for thirty years. Like all of Kon’s heroines, Chiyoko is a “double” figure, onto whom the director projects the biographical and artistic traits of two great icons of Japanese cinema: Setsuko Hara and Hideko Takamine. Through flashbacks, we are gently led — à la Cocteau — into Chiyoko’s past, witnessing her acting career and her lifelong search for a mysterious man with whom she has fallen hopelessly in love. During the interview, the filmmaker and his cameraman “slip” into Chiyoko’s memories, becoming part of them — and so the grand adventure of Japanese cinema turns into an intimate story of memory and dream.

Following the path traced by Perfect Blue, its mirror image, Kon suggests that the cinematic image cannot reproduce “objective reality,” because such a thing does not exist; its true nature is to reveal multiple subjective realities. “In the human heart,” Kon believed, “memories, the present, the past, and the future coexist.” Life unfolds through the freedom and imagination of our perceptions.

The film crew follows Chiyoko through different time periods and genres that pay homage to the great masters of Japanese cinema — Ozu, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, Naruse — forming dazzling love letters to their art. The heroine runs through a “staged” reality where painted backdrops shift like in a Kinoshita film; long takes resolve into subjective time, where years pass in a second; showers of arrows turn into bombs; jidai-geki sets dissolve into landscapes ravaged by World War II. Film posters (What’s Your Name and Love Letter, both 1953) evoke the postwar blend of realism and romanticism. The memory of cinema is an endlessly unspooling reel.

Chiyoko — modeled on Hara, Takamine, and also Kinuyo Tanaka — is the woman of Japanese cinema: a transfigured, beloved, desired being; both the agent of change and the body of sacrifice, yet always ready to live and to love, to hurl herself into an unknown future. The Millennium Actress hides her face in her hands as she weeps, recalling Noriko in Tokyo Story (1953); she rides her bicycle like Hisako in Twenty-Four Eyes (1954); faces the press beside Godzilla (1954); and walks among ruins like Yukiko in Floating Clouds (1955).

Once again, Kon’s boundless ingenuity astonishes — his ability to merge, with emotional force, reality and illusion, cinema and metacinema. He interprets evolving cinematic codes: classical purity becomes the modern “unstable image,” ultimately reaching the realm of the fantastic. Susumu Hirasawa’s score, moving fluidly from romantic piano to electronic unease, helps propel the film into an unreachable dimension — the place where Chiyoko, undeterred by obstacles, becomes the strong and fragile traveler of Love itself:

“After all… it’s the chase I’ve always loved the most.”

Lascia un commento