[Please scroll down for the English version]

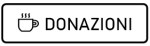

Gin, un alcolizzato di mezza età, Miyuki, un’adolescente in fuga da casa e la drag queen Hana sono un trio di senzatetto che sopravvive come una famiglia improvvisata per le strade di Tokyo. Mentre rovistano nella spazzatura in cerca di cibo la vigilia di Natale, si imbattono in una neonata abbandonata in un bidone della spazzatura. I tre decidono di setacciare le strade di Tokyo per restituire la bambina ai suoi genitori.

Satoshi Kon viene normalmente associato a un’idea di cinema come “infinita macchina dei sogni” e questo porta, talvolta, a sottovalutare lo scrupolo realistico espresso in ogni sua opera: si pensi ai condomini e supermercati di Perfect Blue (1997), all’accurata ricostruzione degli studi cinematografici di Millennium Actress (2001) sino ai quadri urbani di Paranoia Agent (2004) o alla precisione degli interni in Paprika (2006).

Satoshi Kon è fautore di una filosofia degli opposti che vede nella coesistenza di un ineffabile onirismo con un realismo affilato una qualità ineludibile del vivere. Tokyo Godfathers si fa portatore di questa visione in forme nuove, concentrando in un’opera di soli 90 minuti un cinema fiabesco alla Frank Capra, illuminato dalla presenza di angeli imperfetti e umanissimi; un’epica fordiana avventurosa – il viaggio di tre balordi di buon cuore in una frontiera tra margini, quartieri e periferie; e infine una capillare, minuziosa osservazione realistica della città di Tokyo, amata e osservata nel suo reticolo di vicoli, strade, incroci popolosi illuminati da giganteschi manifesti pubblicitari e cinematografici, quasi portali verso un’altra realtà (come già accadeva in Paprika).

Una Tokyo che si fa personaggio affettuoso, complice, animato da spirito protettivo nei confronti dei suoi antieroi smarriti e dolenti, separati dai legami familiari e accolti dall’abbraccio di un ponte, di una baracca, di una panchina o dalle carezze della neve.

Il lavoro di Kon sul paesaggio urbano è intensamente originale: dopo aver catturato infiniti scatti fotografici della città, colta nei suoi angoli meno conosciuti, negli oscuri retrobottega o attraverso inedite prospettive, il regista riproduce “la sua Tokyo” mescolando frammenti di realtà e reinventando nuovi paesaggi partire dalle immagini di riferimento. Il risultato è una Tokyo “più vera del vero”, elaborata e animista: la composizione dell’immagine è effettuata in modo da rendere la città “vivente” e dotata di sentimenti. Un palazzo sembra sorridere, due finestre sono occhi che seguono amorevolmente i protagonisti. Persino una montagna di sacchi d’immondizia viene sottoposta, da Kon e dal suo team di animatori, a un lungo ed estenuante processo di revisione artistica, in modo da ammorbidirne forme e colori. Ogni location, ogni scorcio passa attraverso la fantasia di Kon, che moltiplica i dettagli e crea una Tokyo allo stesso tempo spirituale e iperrealistica attraverso la luce.

Alla città, nitida e viva, infinita nei suoi sfondi labirintici, nelle sue texture stratificate e nella varietà caotica di emozioni di cui si fa portatrice – tra nuovi grattacieli, sentieri nascosti, aree sacre e torii urbani – Kon contrappone la mimica accentuata dei tre stravaganti, ma dolcissimi e determinati protagonisti.

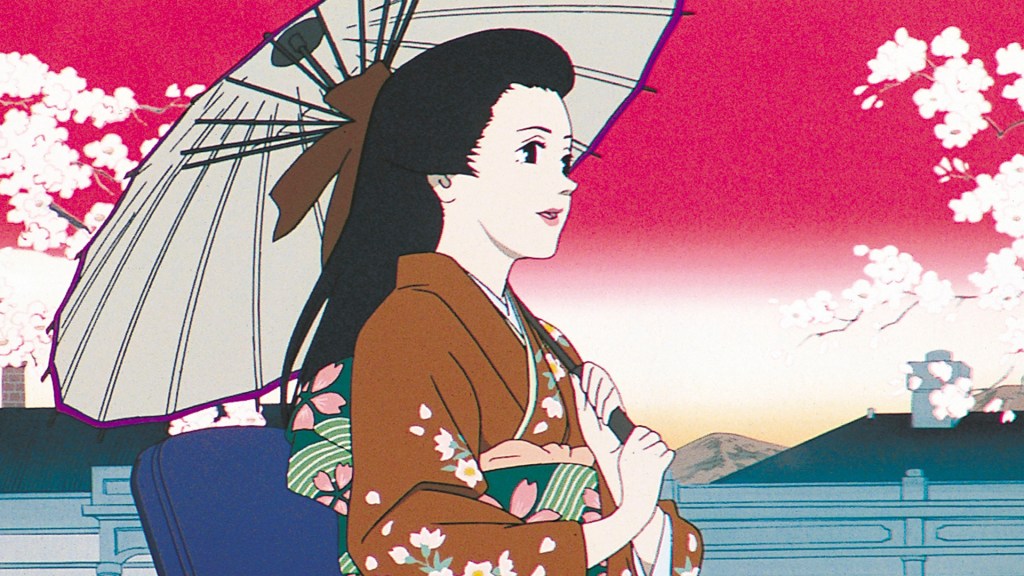

Tokyo Godfathers è, in fondo, un film che reclama la sua classicità e la sua appartenenza al genere classico dello shomingeki, incentrato sulla vita quotidiana delle classi popolari e della gente comune. Così come spesso accadeva nel cinema del passato, anche Tokyo Godfathers volge il suo sguardo compassionevole alle battaglie quotidiane per la sopravvivenza, ai legami affettivi e “selvatici” delle classi più sfortunate, alla malinconia che spesso si tinge di disperata vitalità; e alla presenza di bambini abbandonati, dimenticati, figli “della città” e del suo movimento incessante. Vengono in mente i film di Hiroshi Shimizu, o di Heinosuke Gosho, in particolare Là dove sorgono le ciminiere (1953), con il ritrovamento di un neonato che piange incessantemente dall’inizio alla fine, mentre i personaggi si affannano a cercare nuovi equilibri nelle loro esistenze scombussolate. Ma soprattutto si pensa all’Ozu degli anni ’30, alla sua tenera e disperata umanità delle baracche, a Sakamoto Takeshi nei panni dell’impulsivo e sensibile Kihachi, che sopravvive di espedienti.

I tre protagonisti di Tokyo Godfathers rielaborano l’archetipo dei film di Ozu e lo calano nella metropoli moderna, con le sue violenze (si pensi alla scena dei tre giovani che picchiano i senzatetto) ma anche i suoi angoli d’amore inaspettati (la piccola comunità di immigrati). Tokyo come caos e contraddizione, ma anche come città che sospira d’amore e sogna il ritrovamento dei legami familiari, il perdono e il ricongiungimento anche là dove ogni speranza appariva perduta.

Per questo tableaux di sentimenti Satoshi Kon diminuisce i tagli e predilige il montaggio interno all’immagine; lo spettatore è invitato a perdersi nel labirinto dell’immagine e dei suoi giochi prospettici. Non mancano, inoltre, alcune inquadrature tipiche dell’immaginario di Kon, come ad esempio l’apertura su un “pubblico”, volto a esplicitare la natura della finzione; o come il dettaglio su una mano in primo piano centrale, in una posa arcana e magica.

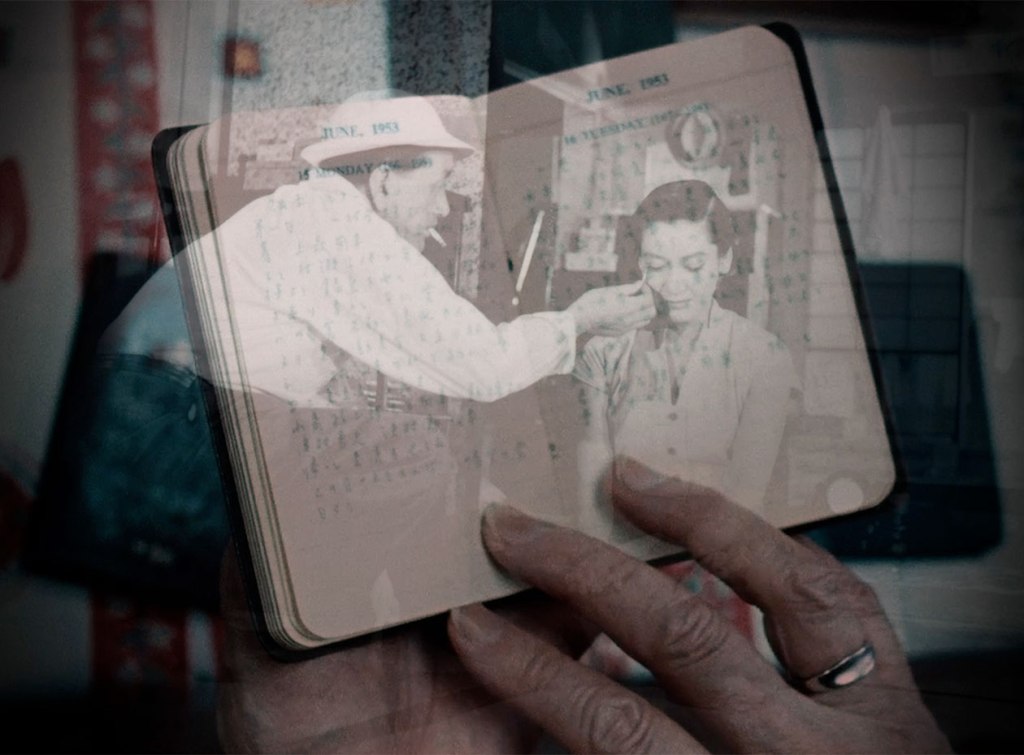

Fondamentale anche la presenza di poster come portali di altre realtà, o di specchi usati come costante riferimento a una duplicità. Ritorna l’ossessione di Kon per il doppio: tutti i personaggi hanno un’altra vita, un passato che li colloca in una differente dimensione, un “altro se stesso” di cui hanno perso le tracce. Un doppio quindi che ha le sue ripercussioni anche sul piano temporale e sul filo interrotto della memoria. In un bar, Kon realizza una sequenza in time-lapse “alla Wong Kar-wai”: i suoi personaggi sono così staccati dal resto del mondo da vivere in un tempo separato e non conforme.

Troviamo, indubbiamente, anche elementi chapliniani, soprattutto nelle gag con il ricco esponente della Yakuza; e un piano sequenza kubrickiano nello slum, con un senso vertiginoso della prospettiva. Tutti segni della cinefilia di Satoshi Kon, un autore dichiaratamente più legato al cinema live action e alla ricerca dei grandi autori della storia del cinema – da Chaplin a Ford, da Welles a Kubrick – che alle coeve sperimentazioni nell’animazione.

English Version

Gin, a middle-aged alcoholic; Miyuki, a teenage runaway; and the drag queen Hana form a trio of homeless people who survive as an improvised family on the streets of Tokyo. While rummaging through the trash in search of food on Christmas Eve, they come across an abandoned baby girl in a garbage bin. The three decide to comb the streets of Tokyo to return the child to her parents.

Satoshi Kon is usually associated with the idea of cinema as an “infinite dream machine,” and this sometimes leads to an undervaluation of the meticulous realism expressed in all his works: think of the apartment blocks and supermarkets in Perfect Blue (1997), the painstaking reconstruction of film studios in Millennium Actress (2001), the urban tableaux of Paranoia Agent (2004), or the precision of the interiors in Paprika (2006).

Satoshi Kon embraces a philosophy of opposites, one that sees the coexistence of an ineffable dreamlike quality with a sharp realism as an unavoidable condition of life. Tokyo Godfathers carries this vision forward in new forms, condensing into just 90 minutes a fairy-tale cinema reminiscent of Frank Capra, illuminated by redemption and by the presence of imperfect, deeply human angels; a Fordian, adventurous epic — the journey of three good-hearted misfits across a frontier of margins, neighborhoods, and outskirts; and finally a capillary, meticulous realist observation of the city of Tokyo, loved and examined in its web of alleyways, bridges, streets, and bustling intersections lit by gigantic advertising and film billboards, almost portals to another reality (as already seen in Paprika).

A Tokyo that becomes an affectionate character, a conspiratorial presence animated by a protective spirit toward its lost and aching antiheroes, cut off from their family ties and welcomed by the embrace of a bridge, a shack, a bench, or by the caress of falling snow.

Kon’s work on the urban landscape is intensely original: after capturing countless photographs of the city — glimpsed in its lesser-known corners, its dark back rooms, or through unexpected perspectives — the director recreates “his Tokyo” by blending fragments of reality and reinventing new landscapes from the reference images. The result is a Tokyo “more real than real,” elaborated and animistic: the composition of each frame is designed to render the city “alive” and endowed with feeling. A building seems to smile; two windows act as eyes lovingly following the protagonists. Even a mountain of garbage bags is subjected, by Kon and his team of animators, to a long and exhausting artistic revision to soften its shapes and colors. Every location, every glimpse of the city passes through Kon’s imagination, which multiplies details and creates a Tokyo that is both spiritual and hyperrealistic through its light.

To this sharp and vivid city — infinite in its labyrinthine backgrounds, its layered textures, and its chaotic variety of emotions, from new skyscrapers to hidden paths, sacred areas, and urban torii — Kon contrasts the accentuated expressiveness of the three eccentric, yet sweet and determined protagonists.

Tokyo Godfathers is, at its core, a film that asserts its classicism and its belonging to the traditional shomingeki genre, centered on the daily lives of working-class people and ordinary folk. As often happened in the cinema of the past, Tokyo Godfathers turns its compassionate gaze toward the daily battles for survival, the “wild” and affectionate bonds of the less fortunate, the melancholy that is often tinged with desperate vitality, and the presence of abandoned or forgotten children — “children of the city” and of its incessant movement. One is reminded of the films of Hiroshi Shimizu or Heinosuke Gosho, especially Where Chimneys Are Seen (1953), with its discovery of a baby who cries incessantly from the first to the last frame, while the characters struggle to find new balance in their unsettled lives. But above all, one thinks of Ozu in the 1930s, of his tender and desperate humanity of the shantytowns, of Sakamoto Takeshi as the impulsive and sensitive Kihachi, surviving by his wits.

The three protagonists of Tokyo Godfathers rework the archetype found in Ozu’s films and set it within the modern metropolis, with its violence (consider the scene with the three youths attacking the homeless) but also its unexpected pockets of kindness (the small immigrant community). Tokyo as chaos and contradiction, but also as a city that sighs with love and dreams of recovering family bonds, of forgiveness and reconciliation even where all hope once seemed lost.

For this tableau of emotions, Satoshi Kon reduces cutting and favors internal montage within the frame; the viewer is invited to lose themselves in the labyrinth of the image and its perspectival games. There are, moreover, several shots typical of Kon’s imagery, such as the opening on an “audience,” meant to make the nature of fiction explicit, or the close-up of a hand in the center of the frame, posed in an arcane, magical gesture.

Equally fundamental is the presence of posters as portals to other realities, or of mirrors used as constant references to duality. Kon’s obsession with the double returns: all the characters have another life, a past that places them in a different dimension — an “other self” whose traces they have lost. This doubling also has repercussions on time itself and on the broken thread of memory. In a bar, Kon stages a time-lapse sequence “in Wong Kar-wai style”: his characters are so detached from the rest of the world that they inhabit a separate, nonconforming time.

We also find, undoubtedly, Chaplinesque elements, especially in the gags with the wealthy Yakuza figure; and a Kubrickian long take in the slum, with its vertiginous sense of perspective. All signs of Satoshi Kon’s cinephilia, an author openly more tied to live-action cinema and to the legacy of the great filmmakers of film history — from Chaplin to Ford, from Welles to Kubrick — than to contemporary experiments in animation.

Lascia un commento